Tuesday, August 31, 2004

Footloose in LA and a Couple Links

But before I join the traffic jam that they call the 405 out here, I thought I would post a couple pointers.

Via ArtsJournal, The Los Angeles Times reports that Clear Channel's next touring museum exhibition, "Troy," will feature a large wooden Trojan horse. The article says:

Indeed, detractors may find it tartly amusing that Clear Channel wants to deliver a Trojan horse to museums' doorsteps. To them, the corporate equivalent of pillage and burn has been the company's battle plan since 1996, when the then-modest outfit from San Antonio began a buying spree.Clear Channel gets no points for subtlety.

Tyler Green at Modern Art Notes is back from vacation and promises more notes this week on his art trek through the Southwest. My take on his first post?

Best indication that Tyler Green isn't from New York: A real New Yorker would view the rats outside SITE Santa Fe's Grotesque biennial as atmosphere.

Sunday, August 29, 2004

On the Road, Not on Line

I'm on the road for the day job, humping through more airports than I care to count, and carrying a suitcase that holds way too many clothes for the number of days I'm away. (Do people in Phoenix really wear suits to business meetings when the day's high temperature is predicted to be 109 degrees? I guess I'll find out.)

I may have time for a post or two, and I've got high hopes to see some art with a couple of free hours I have in LA. But don't count on a daily post this week.

In the absence of content from me, why don't you read the fine print from today's march in New York.

Friday, August 27, 2004

Here Come the Republicans, and the Art is Ready

Smith's article highlights a small show called "Republican Like Me" at Parlour Projects in Williamsburg. When discussing this show, Smith focuses on Rachel Mason's plaster sculpture Kissing President Bush, a color photo of which is given all the space above the fold of today's Fine Arts section.

I saw the show last Sunday and was sorry to see that Smith didn't mention one of the artists in it, Esperanza Mayobre. Through the magic that she works, Mayobre has gotten the U.S. government to forgive the debt of all third-world nations. The leaders of these countries are so grateful to her that they have put her picture on their currency. Mayobre's piece consists of photos of a host of third-world leaders saluting her for her good deed and a massive pile of Venezuelan 1000 Bolivar notes with her picture on them.

Since art theft has been on my mind this week, I was tempted to make a trip back out to the show to grab a handful of the bills. I am flying through JFK next Monday, and I was thinking about trying to change them into American cash at a currency exchange booth before I catch my flight. (What are the chances that the people manning these booths know what a real 1000 Bolivar note looks like?) Having dreams of seriously upgrading my stay in Los Angeles, I just went looking for the Bolivar-Dollar exchange rate to see how many bills I would need to nab to be able to check into the Four Seasons in Beverly Hills for the week. It turns out that 1000 Bolivars are worth 52 cents. Maybe I'll try Saturday's Lotto drawing instead.

I first saw Mayobre's work in a group show earlier this year at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. She recently finished preparatory work for an installation for a small space in my apartment. I'm hoping that by the time I'm back from the west coast next week she will have been able to install the piece. That, and the fact that the Republicans will be gone by then, would be a nice welcome home after a long trip.

Thursday, August 26, 2004

Getting Snarky on the NEA

If Gioia thinks his old neighborhood needs a real arts institution, he ought to send some pork home from Washington to get the ball rolling instead of whining in the local paper. Killing off his silly “Shakespeare in American Communities” program would free up enough NEA capital to provide seed funding for a decent art museum or theater company back home.

I might feel differently about Gioia’s Shakespeare for the Provinces project if I thought that the target audiences for these performances would be able to draw a connection between our country’s current head of state and the political leaders in Shakespeare’s tragedies. (I’m thinking, specifically, of Macbeth’s vaulting ambition and eagerness to take counsel from untrustworthy advisors, Hamlet’s madness caused by a conflicted desire to revenge his father, and Lear’s series of just-plain-bad decisions that lead his kingdom into chaos.) But I'm not that optimistic about the conceptual abilities of my fellow citizens.

Arts patrons and funders of the type Gioia seeks (and I’m excluding from this class the new crop of collectors who are opening vanity museums around the country) turn up only a couple times in each generation. Those of us who live in cities fortunate enough to have benefited from their largess (places like Cleveland, Washington DC, Toledo, and New York) should be thankful we’re not reliant on the NEA to deliver our cultural experiences for us.

With the head of the NEA out begging for someone to turn the key to start culture in his home town instead of using the resources at his disposal to do it himself, we can see how ineffective the government’s attempts at supporting the arts have become.

Wednesday, August 25, 2004

What a Difference Ten Weeks Makes

I figured that if the blogger had been there he must have gone on to the Jetty too. So I started digging through his archives. Sure enough, he has some fabulous photos available from a visit he made in early June.

I was astounded to see the Great Salt Lake's change in water level over just ten weeks. These photos taken the first week in June show water surrounding Spiral Jetty. During the second week in August when I made my visit, Spiral Jetty was surrounded by a giant salt flat.

To see the photos on While Seated for yourself, jump over to here, here, here, here, and here.

Monday, August 23, 2004

Proposed Security Enhancements in Light of the Munch Theft

In the theft on Sunday, two robbers, wearing dark ski hats over their faces, burst into the Munch Museum in Oslo at 11:10 a.m. and threatened unarmed guards with pistols, the police said.This wasn't the typical cloak-and-dagger, highly-planned, after-hours heist that comes to mind when I think of art theft. This was a B-grade bank robbery that occurred in a museum. Combine this incident with the theft last summer at Drumlanrig Castle in Scotland, and you have the basis for what might become a trend.

Speaking in Norwegian, one of the men held two guards at gunpoint, ordering them to the floor, while the other used a wire cutter to clip the framed paintings free of the wall, museum officials said. Witnesses described the thieves as clumsy, even dropping the paintings on the way out.

As if they didn't have enough to worry about already, now museum directors need to ensure that their security strategies cover potential daytime hijacking of the works in their collections.

In the spirit of helpfulness, I thought I would propose a few new security policies to help protect against the kind of theft that occurred at the Munch Museum. For starters, every museum ought to adopt these new safeguards:

- Visitors wearing ski masks should not be admitted to the galleries.

- Visitors should kindly be asked not to bring firearms into the building.

- Local police should be informed if security sees what appears to be a getaway car idling near the building entrance, especially if the driver is wearing a ski mask.

- Richard Serra at Beacon: Staff should be especially vigilant about trains with flatbed cars stopping on the railroad tracks that run alongside the building. If a train of flatbed cars is stopped there, and if a crane is spotted approaching the museum, local police should be called immediately.

- Robert Smithson at Beacon: Visitors should no longer be allowed to bring Shop-Vacs with them into the building.

- Fred Sandback at Beacon: Watch closely visitors who have knitting needles in hand while in the galleries. Be suspicious of visitors attempting to leave the building wearing sweaters during summer months.

- Dan Flavin at Beacon: From now on, electricians contracted to change light bulbs in the building must be escorted by museum staff as they make their rounds.

- Walter De Maria, The New York Earth Room in SoHo: If dumptrucks and a backhoe are seen idling on Wooster Street, immediately notify the local NYPD precinct house.

Friday, August 20, 2004

Perspective

Making the trip to see Spiral Jetty forced me to see the work through a much wider lens, giving me a new appreciation for the work and its context.

Visiting Spiral Jetty showed me the dialogue the piece has with its environment in a way that critical essays and photo documentation have not. Interestingly, this isn’t the case for all Earthworks. Walter De Maria’s Lightning Field relates to its environment in a much different way than Smithson’s Spiral Jetty. The Lightning Field does not engage with its surroundings. It consumes them, making the vista to the horizon in every direction a part of the piece. There are no distractions in the environment, and no dialogue with it, because at The Lighting Field everything seen, felt, and experienced becomes a part of the work.

Spiral Jetty is not like that. Although still a monumental construction, it is much smaller than the Lightning Field and is much more discrete. It doesn’t annex the landscape, sucking it in and claiming it. The landscape dwarfs Spiral Jetty, and the natural and man-made features seen from Spiral Jetty open a dialogue with the work.

Spiral Jetty is not like that. Although still a monumental construction, it is much smaller than the Lightning Field and is much more discrete. It doesn’t annex the landscape, sucking it in and claiming it. The landscape dwarfs Spiral Jetty, and the natural and man-made features seen from Spiral Jetty open a dialogue with the work.

The industrial site to the east, with its larger jetty, provides the “entropic landscape” for Spiral Jetty, surrounding it with detritus rotting away with time. From Spiral Jetty you can see this other jetty—the two opening a sort of dialogue about the reasons that humans have made incursions out from the shore into the Great Salt Lake.

Other traces of human use of the land and sky are evident. The hill to the north of the jetty, the place to get an aerial view of the work, is covered with drying cow dung. The landscape here is still used for productive purposes; today it produces cattle instead of barrels of oil.

The land around Spiral Jetty is also scarred with traces of past rail transportation. The transcontinental railroad was completed 16 miles from Spiral Jetty, and there are many historic railroad grades in the area. No longer used, their tracks ripped up in the early 1940s to feed the war machine, these deep cuts and fills in the landscape are still clearly visible and speak to the history of man using the land, carving into it, for his own purposes.

Overhead, today, the clear blue sky is filled with the contrails of airplanes flying east to west and south to north over Spiral Jetty. As remote as the site may feel on the ground, civilization still moves around and above it through the air.

There has been talk since Spiral Jetty reemerged about conserving it somehow. The man who led the construction crew that created the jetty has said that in the past he’s been tempted to take his machinery back to the site to pile on more dirt and rock, to bring the piece back to life. But, he said, he’s decided against this because it wouldn’t be the same without Smithson’s involvement.

There has been talk since Spiral Jetty reemerged about conserving it somehow. The man who led the construction crew that created the jetty has said that in the past he’s been tempted to take his machinery back to the site to pile on more dirt and rock, to bring the piece back to life. But, he said, he’s decided against this because it wouldn’t be the same without Smithson’s involvement.

I think he has the right idea. Dia, which is now responsible for the piece, should monitor it (perhaps more closely than they do today) but should allow nature to continue taking its course. It would be desirable for Dia to take steps to limit the damage that visitors are doing to Spiral Jetty (perhaps removing some of the signage to the site, requiring visitors to sign in at the Golden Spike Visitor’s Center to receive a map, and asking them to agree to follow a leave-no-trace ethic during their time there), but intervening on the work itself in any way would not be right. Nature should be allowed to work on the piece, changing Spiral Jetty’s character over time.

Over the next year or two, the Great Salt Lake will continue to evaporate, turning lake into salt flat, further locking Spiral Jetty in its dry, frozen grip. But at some point in the future the rains will come again, the lake will rise, the waters will encircle (and eventually cover) the work.

Over the next year or two, the Great Salt Lake will continue to evaporate, turning lake into salt flat, further locking Spiral Jetty in its dry, frozen grip. But at some point in the future the rains will come again, the lake will rise, the waters will encircle (and eventually cover) the work.

Spiral Jetty, present now—dry as can be—will disappear, existing as memory and documentation for several years. But someday again it will reemerge, different somehow yet still fascinating to those interested enough to drive to the end of the road on Rozel Point to seek it out.

It’s a cycle we have experienced in our generation, and a cycle that generations in the future should be able to experience as well.

Previous: Walking the Jetty

Thursday, August 19, 2004

Walking the Jetty

Once you've picked your way down the incline to the (former) shore of the Great Salt Lake and the base of Spiral Jetty, though, the piece looks larger. Then you take your first steps onto it.

As you walk, you begin to appreciate the true size of the piece and realize that your first impression was not correct. This thing is big. The initial run out from shore is straight. Eventually, it begins to curve to the left and, if you are walking the whole spiral, you start to circle around and fall in towards the middle.

As you become adjusted to the harsh surroundings, you begin to notice details: How the piece appears well on the way toward melding with its environment. How a few of the tallest rocks are not encrusted to their tops. (Were these always sticking above water?) How the salt has attached itself to the rocks, forming stalactites and stalagmites on the edges of the jetty. How the salt has bonded so strongly to the rocks that it's impossible to scrape or kick it off.

You also begin to see that the entropy at work here at Spiral Jetty is not all natural. There is evidence all around that people are using the site in ways that will lead to its disintegration over time. People (probably men based on the expressionistic traces left) have pissed all over the work--on the sides of the boulders, on the top of the jetty, and (most prominently) right at the tip of the spiral--staining the white salt yellow. There are several piles of shit on the jetty and on the hard salt surface around the piece. At the tip of the jetty someone has left what was probably once a small sculpture made of modeling clay. It's now disintegrated into a puddle of red, blue, yellow, and green mush that looks like a melting scoop of Superman ice cream. There are cigarette butts on the jetty and empty cans at its base.

Leaving the work behind for a few minutes, you can walk another 75 meters out on the salt flats before you reach the waterline. Smithson chose this location, in part, for the red tint in the water. The water takes on a rusty hue right at the shoreline, but turns a gentle pink as you walk farther away from shore. There is no drop off here. It feels like you could walk, no greater than ankle deep in the salt water, all the way to the horizon.

But it's not possible to stay out for that long. Here, at almost a mile above sea level, the sun is brutal. And the light reflected off the pure white salt flats only increases its power. After a half hour you begin to feel like you are drying out. You start to worry that you'll dessicate completely, your last motion frozen in a casting of salt. You see that this has happened here before.

It's time to return to the shade of the car. (There isn't shade anywhere else.) But maybe one more walk on the spiral first.

Previous: Industrial Wasteland

Next: Perspective

Wednesday, August 18, 2004

Industrial Wasteland

It would have been possible to miss a turn or a fork in the road out on the plain, but this landmark is impossible to miss.At this gate the Class D road designation ends. If you choose to continue south for another 2.3 miles, and around the east side of Rozel Point, you should see the Lake and a jetty (not the Spiral Jetty) left by [an] oil drilling exploration in the 1920s through the 1980s. As you approach the Lake, you should see an abandoned, pink and white trailer (mostly white), an old amphibious landing craft, an old Dodge truck...and other assorted trash.

From this location, the trailer is the key to finding the road to the Spiral Jetty. As you drive slowly past the trailer, turn immediately from the southwest to the west (right), passing on the south side of the Dodge, and onto a two-track trail that contours above the oil-drilling debris below. This is not much of a road! Only high clearance vehicles should advance beyond the trailer. Go slowly! The road is narrow, brush might scratch your vehicle, and the rocks, if not properly negotiated, could high center your vehicle. Don't hesitate to park and walk. The Jetty is just around the corner.

Since the directions to the site were written (since, even, last summer based on pictures I've seen from 2003), the trailer has moved one step closer to being just a pile of rubble. The walls are gone, and pieces of the appliances are strewn about. It's now little more than a room with a view. Quite a view.

The refuse on the site isn't limited to the trailer. And it's clear that the junk here isn't going anywhere soon.

It's fitting that the most prominent landmark on the drive to Spiral Jetty is the decaying traces of industrial activity. Smithson was interested in what he called the "entropic landscape," a landscape marred by human industrial intervention that exhibits signs of decay and degradation. This interest provides the conceptual basis of his earlier Non-site works. In a 1972 interview with Paul Cummings for The Archives of American Art, Smithson had this to say about his move to working out-of-doors and his selection of locations based on their use as industrial sites:

CUMMINGS: But by the late sixties everybody worked out[side] of the buildings.Smithson sited Spiral Jetty in exactly one of these landscapes, a fact that is important to the work but that is usually glossed over in discussions of it.

SMITHSON: Yes. Well, there was always this move toward public art. But that still seemed to be linked to large works of sculpture that would be put in plazas in front of buildings. And I just became interested in sites.... I guess in a sense these sites had something to do with entropy, that is, one dominant theme that runs through everything. You might say my early preoccupation with the early civilizations of the West was a kind of a fascination with the coming and going of things.... And I became interested in kind of low profile landscapes, the quarry or the mining area which we call an entropic landscape, a kind of backwater or fringe area.

Interesting, as well, is the fact that Smithson's is not the only jetty in the area. The oil drilling operation had used a jetty before Smithson and his construction crew arrived on the scene. This jetty, a non-spiraled jetty, stretches out into the Great Salt Lake for over a quarter mile. It's still very much present and still shows traces of how it was used. There is a parking area at its foot, a drivable roadway running onto it, and more industrial detritus strewn around it.

This jetty is a mere half mile east of the site Smithson selected for his work and is clearly visible from Spiral Jetty. The satellite photo included in the Sculpture article on Spiral Jetty shows how closely situated these two objects are and how much larger than Smithson's this jetty is.

Seen in the context of its location, the significance of Spiral Jetty becomes more layered and nuanced. Smithson combined an archetypal symbol (the spiral) used by early civilizations of the West with the vernacular of this "entropic landscape" (the jetty) to create a piece that both complements and comments on the anthropological and industrial history of the site. Smithson's jetty, though, unlike its cousin to the east, curves back in on itself, goes nowhere, and exists not for the purpose of extracting energy from the Great Salt Lake but for the purpose of contemplation. Seen through the lens of Kantian aesthetics, it's as pure an art work as any object can be.

But unlike most works of art, you can walk on this one. And, as the directions say, Spiral Jetty is just around the corner from here.

Previous: Drive to the Jetty

Next: Walking the Jetty

Tuesday, August 17, 2004

Drive to the Jetty

Journeying to the site is as much a part of the experience as actually seeing the work, and historically it has been difficult both to travel to the site and to find the piece. These resistance points, though, have disappeared in recent years. With the drought in the west leading to falling water levels in the Great Salt Lake, the work emerged from submersion a couple years ago, allowing visitors to see it for the first time in decades. And as more and more visitors made the trip out to the work, the Utah Department of Natural Resources decided to provide signage to help drivers locate the piece.

The most prevalent directions to the site lead you to believe that you'll need to count cattle guards and miles in order to find Spiral Jetty. That's not the case anymore. Simply make your way to the visitor's center for the Golden Spike National Historic Site. The visitor's center is located 25 well-signed miles west of exit 368 on I-15, which is 65 miles north of Salt Lake City.

Once you arrive at the visitor's center, the real journey begins. At the parking lot for the building, the paved road ends and the signage for Spiral Jetty begins.

Once you pass the parking lot, you leave behind the RVs and families of tourists and enter working ranch land. The vistas are stunning. The roads run straight and long, the sky feels gigantic, and your eye starts to accustom itself to focusing on the infinite. You feel small.

There is not much moving in the arid, sun-beaten landscape, and there is no shade. Every so often a water tank pops up near the road, but I did not see any cattle on the 16 mile drive from the visitor's center to Spiral Jetty. On the way back, though, I had to stop the car as a herd of wild horses crossed the road, trotting single-file off toward the horizon.

Occasionally the road will fork, one branch going on to Spiral Jetty, the other going to who knows where. All these places are now signed. Missing a turn could make for a very long day of driving (there's no one out there to ask for directions) under a merciless sun.

You know you're getting close to the end of the road when you finally reach the shore of the Great Salt Lake and see the remnants of an old, unsuccessful oil drilling operation.

Previous: Back from Spiral Jetty

Next: Industrial Wasteland

Monday, August 16, 2004

Back from Spiral Jetty

I’m back from my quick trip to Utah to see Spiral Jetty. I will probably post something more thought-based on the piece and the experience of visiting it later this week. I will definitely post more photos in upcoming days. But I thought I would stick some facts and a few snapshots up today to give more current information than is available elsewhere on the Internet about accessing the site and current water levels.

I’m back from my quick trip to Utah to see Spiral Jetty. I will probably post something more thought-based on the piece and the experience of visiting it later this week. I will definitely post more photos in upcoming days. But I thought I would stick some facts and a few snapshots up today to give more current information than is available elsewhere on the Internet about accessing the site and current water levels.

First off, it’s not as difficult to get to Spiral Jetty as I had thought. If you can find your way to the north bound lanes of I-15 in Salt Lake City (not I-80 as most direction you’ll find on the Internet say), you can find your way to Spiral Jetty. There is signage on I-15 for the exit to Golden Spike National Historic Site (exit 368). The roads to Golden Spike are well signed once you exit the interstate, and as you pull up to the parking lot at the Golden Spike visitor’s center you see the first sign to Spiral Jetty. Major intersections (as major as one-lane dirt road intersections can be) for the rest of the 16 mile drive out to Spiral Jetty are signed as well. There’s no need to worry about counting cattle guards and measuring miles. While the last mile of road is rough, in dry conditions it’s not necessary to use a four-wheel-drive or high-clearance vehicle to get to Spiral Jetty.

First off, it’s not as difficult to get to Spiral Jetty as I had thought. If you can find your way to the north bound lanes of I-15 in Salt Lake City (not I-80 as most direction you’ll find on the Internet say), you can find your way to Spiral Jetty. There is signage on I-15 for the exit to Golden Spike National Historic Site (exit 368). The roads to Golden Spike are well signed once you exit the interstate, and as you pull up to the parking lot at the Golden Spike visitor’s center you see the first sign to Spiral Jetty. Major intersections (as major as one-lane dirt road intersections can be) for the rest of the 16 mile drive out to Spiral Jetty are signed as well. There’s no need to worry about counting cattle guards and measuring miles. While the last mile of road is rough, in dry conditions it’s not necessary to use a four-wheel-drive or high-clearance vehicle to get to Spiral Jetty.

As of this past weekend (these photos were taken on August 14, 2004) Spiral Jetty is not only above water, it’s completely land locked. The Great Salt Lake has receded so much that the water line is currently 75 meters beyond the edge of the piece that is most distant from shore.

I took several panoramic shots of the piece to try to capture it in as much of its natural context as possible. Here's a sample of some of the photos that will follow.

Update: In the interest of sharing a number of pictures but in keeping individual post sizes down, I've decided to post four follow-ups to this item over the next few days. They will be called:

As I complete each post, I will provide a link to it above.

Thursday, August 12, 2004

On the Way to Spiral Jetty

From the Floor will be silent for the next few days--at least until Monday--as I'm heading out the door on a short trip.

From the Floor will be silent for the next few days--at least until Monday--as I'm heading out the door on a short trip.

That's the bad news.

The good news is that when I return I'll have photos and a report on the current state of Spiral Jetty. As I mentioned in an earlier post, I made plans last month to travel to the Southwest to see another of the major Earthworks.

From what I can gather, the water level of the Great Salt Lake is still low enough to allow the piece to be seen. I'm not sure, though, if the level is so low that there will be no water surrounding the work. I got the impression from some photos I saw over a year ago that this was the situation.

In the interim, here are a few links to sites and recent articles on Robert Smithson's most well known piece.

- Dia's website for the work

- The estate's website for the work

- The July/August issue of Sculpture has a good article (including the directions that I'll be following to get there)

- Last weekend, The Telegraph published a short article on the current state of Spiral Jetty.

The Telegraph's article is a review piece that doesn't really say much--but it does say it well. Except, that is, for the part that claims:

like Herman Melville, author of Moby Dick, Smithson was a great American pessimist (almost as marked a feature of the national psyche as can-do optimism).

Whatever. After all these centuries the Brits still have a hard time understanding us Yanks and our canonical authors.

Stop back Monday night or Tuesday when I've had the opportunity to upload some photos.

The Utopia That Can't Be Realized

His large photo Night Revels of Lao Li is one of the centerpieces of the ICP portion of the show. It embodies most of the ideas the curators wanted to explore with the exhibition: rapid social change, engagement with history in this new era, the cultural hybridity created with the collision of east and west, and the reworking of traditional artistic forms in new media. (Wang makes an image of this piece available on his website along with a reproduction of the scroll painting that inspired the work.)

The new issue of NYFA Current presents an interesting essay by Wang as part of its In Their Own Words feature. Wang discusses the instigating ideas for his work, his working method, and details about the creation of two recent pieces--China Mansion and Romantique.

He closes the essay with this sentence:

Like in China Mansion, the communication in Romantique is forced, manufactured, chaotic, and confusing--a fabricated prosperity and happiness, like a utopia that can't be realized.His closing remark, about a utopia that can't be realized, struck me as being an apt epithet for both the exhibition and the current state of Chinese culture. Marxism didn't bring the utopia that was promised, and now capitalism is beginning to show its failures as well. The artists in Between Past and Future may be some of the first to highlight this fact for the world.

Aerial Photos Worth Seeing

I have no idea what this site is, but the photos it presents are stunning eye candy. If anyone reads Japanese (at least I think that's Japanese), please drop me an email to let me know what this page is all about.

Wednesday, August 11, 2004

Clyfford Still for Denver

The article ends with this sentence, "The mayor said several factors clinched the deal, including the city's vow to truly honor Still's accomplishments."

Now, what do you suppose that means? How does Denver plan to "truly honor Still's accomplishments"?

Here's my best guess of things that the city had to promise Patricia Still to close the deal:

- A new Claes Oldenburg sculpture of a palette knife will be commissioned for the entrance to the museum building that will be constructed.

- Until a suitable museum is built to present his work to the public, Still's paintings will be hung in the court house where the Kobe Bryant trial is being held. Lighting will be designed to make them look especially pretty for the TV cameras.

- From this day forward in the city of Denver, August 10 will officially be known as "We Honor Clyfford Still's Accomplishments Day."

- A special commemorative series of Coors Light cans will be printed with images of Still's paintings.

- Loans from the collection of Still's work will be prohibited, as will displaying work by any other artist. (No, wait, they actually did promise that.)

- The Denver Art Museum will deaccession all artwork made after 1930 by artists whose last name is not "Still."

- The city will change its tag line from "The Mile High City" to "The Impasto Capital of the World."

- You know that mountain range off to the west of the city? There's no reason those can't be called the Clyfford Mountains, is there?

What Google Knows

I thought I would spin the challenge a slightly different way. Instead of coming up with my own top ten list, I asked Google for its top answer to ten arts related questions.

I thought I would spin the challenge a slightly different way. Instead of coming up with my own top ten list, I asked Google for its top answer to ten arts related questions.

Follow the links below to see where Google will send you if you type each question into its main search page and hit the "I'm Feeling Lucky" button.

- Who is the world's greatest living artist?

- Who is the most significant living American painter?

- Who is America's most important living sculptor?

- What is the best painting ever painted?

- What are the best artworks ever made?

- Who is today's most insightful art critic?

- Who is America's hottest curator?

- Which one is North America's finest art museum?

- America's most important gallery?

- America's most influential gallery?

And as a special bonus offering, in case you were wondering:

Tuesday, August 10, 2004

A Note for Columbia University's IT Department

You might want to check out the main web page for the MFA in visual arts program. Some jokers have hacked the page and replaced the "Message from the Chair Video" with a spoof.

Don't get me wrong; I'm not anti-spoof. I have a history of pulling off some good ones myself. But this one is so bad that it ought to be taken down right away.

What's that? It's not a spoof? You're serious? You mean, the chair of the department actually did this? And he still has a job with the university?

Tenure. It's a terrible thing to waste on academics.

What Happened to Art Criticism?

Modern Kicks' review of James Elkins' pamphlet What Happened to Art Criticism? intrigued me enough to make me pick up a copy of the little book for myself. I was able to get through it in a short sitting over the weekend.

Modern Kicks' review of James Elkins' pamphlet What Happened to Art Criticism? intrigued me enough to make me pick up a copy of the little book for myself. I was able to get through it in a short sitting over the weekend.

The pamphlet exhibits what is admittedly provisional thinking on the topic. Modern Kicks and others have pointed out some weaknesses that I hope will be strengthened when the material is published as part of a larger work in the future.

That said, for those who are interested in writing about art, the book does prove useful. It presents three frameworks for thinking about the craft (what's being done today, what won't work for fixing the weaknesses seen in these approaches, and what Elkins would like to see more of in the craft) that prove useful enough to pay back the inexpensive sticker price and the 75 minutes the book takes to read.

If nothing else, the book will force you into a heightened state of self-awareness as you write about what you've seen. And that can never be a bad thing.

Always Wear a Rain Hat when Viewing Chicago Architecture

Monday, August 09, 2004

Photography from East to West

To people who look at a lot of contemporary American art, the works in this show will feel very familiar. The photos and videos in these installations include all the hallmarks of current domestic photographic practice—documentation of performative action and creation of elaborately staged scenes. They also display a deeply seated concern with the body and identity.

This last area, though, is where the work begins to depart from the familiar. Instead of filtering identity through race, class, and gender, these artists tend to explore issues of identity through the lenses of political ideology (specifically the legacy of the Cultural Revolution—the era during which most of them grew up) and China’s drastic societal change of the last two decades.

It may not be a stretch to claim that no human culture (except those that have experienced genocide) has undergone a more fundamental transformation in such a short period of time as Chinese culture has since the mid-1980s. That transformation, and the physical and psychological dislocations it has caused, is seen in much of the work shown here.

Pieces selected for the exhibition have been categorized according to four themes. Two themes are shown at ICP and two at the Asia Society. ICP presents “People and Place” and “Performing the Self” while the Asia Society hosts “Reimagining the Body” and “History and Memory.” The Asia Society’s portion is much smaller than ICP’s (works are contained in a single small Asia Society gallery), but the works shown at the Asia Society tend to be more engaging and compelling than those at ICP. For the interested viewer on a budget (yes, it does require two separate admissions to see both parts of the show), a personal preference for quality vs. quantity should determine which half to see.

Although I’ve just aligned the ICP’s portion of the show with quantity, that doesn’t mean there’s an absence of quality work on display. The floor devoted to “People and Place” contains several works that highlight the rapid transformation of China’s urban landscape. Wang Jinson’s City Wall is five panels containing 1000 small photographs shot from a car as he drove around urban locations. Recent buildings, anonymous high rises for the most part, are presented as black and white images. Strewn among the homogeneity are occasional color snapshots showing traces of the ancient structures that are rapidly disappearing. These buildings and architectural details pop out of their black and white context like surprise glimpses of something unique caught from the corner of the eye.

Although I’ve just aligned the ICP’s portion of the show with quantity, that doesn’t mean there’s an absence of quality work on display. The floor devoted to “People and Place” contains several works that highlight the rapid transformation of China’s urban landscape. Wang Jinson’s City Wall is five panels containing 1000 small photographs shot from a car as he drove around urban locations. Recent buildings, anonymous high rises for the most part, are presented as black and white images. Strewn among the homogeneity are occasional color snapshots showing traces of the ancient structures that are rapidly disappearing. These buildings and architectural details pop out of their black and white context like surprise glimpses of something unique caught from the corner of the eye.

Working with the same theme, Zhang Dali paints graffiti-style heads on old buildings marked for demolition to make way for new construction. He then cuts out the form with a chisel and photographs the result. In his work we see either the new urban landscape or another historic building destined for destruction framed through the face-shaped aperture.

At the Asia Society Xu Zhen includes a piece in the “Reimagining the Body” section that uses Post-it Notes printed with black and white fragments of the body (obtained from pornographic Internet sites) to comment on the disintegration of the individual as a result of the information age that has swept through China and the western world. The curatorial note next to the work encourages viewers to move the hundreds of individual pieces around to new locations on the wall, creating a new order from the fragmentation that exists without bringing any sort of unity to the whole. The work highlights the state of dislocation experienced by individuals in a society that has undergone a wholesale psychological and physical transformation during a single generation.

Ma Liuming places this societal transformation in the broader context of Chinese history. Embodying a female alter-ego (Fen-Ma Liuming), the artist strips naked, effectively becomes a transgendered individual, and walks along remote portions of the Great Wall. The history and solidity of the wall is contrasted with the fragility and transitory nature of the individual in a contemporary society that has undergone significant transformation.

The exhibition (on display in New York through September 5, 2004 and then traveling to Chicago, Seattle, Berlin, and Santa Barbara) presents a first view for many in the west of what several critics and scholars believe will be the next frontier for the avant-garde during the twenty-first century. It’s an opportunity that shouldn’t be missed for those who care about contemporary art.

Sunday, August 08, 2004

Ryan McGinley Goes to the Pool

This work lacks the spontaneity and joy seen in the photographs of his unclothed friends cavorting in the water, but it does present a view of these aquamen and women that will be a nice tonic in upcoming weeks. When, after the games begin, you reach a point where you've had your fill of seeing these athletes presented as red, white, and blue draped heroes collecting medals in the name of freedom, democracy, and homeland security, take a trip back to the Times site to get a fresh view of them through McGinley's eye.

The Times website has made McGinley's published portfolio available online. Also included is a second group of photos with material that did not appear in print.

Saturday, August 07, 2004

Lee Bontecou's Contemporary Baroque

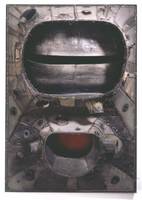

The Lee Bontecou exhibition at MoMA QNS (through September 24, 2004) hinges on a work from 1966. Hung in the middle of this chronologically installed show, the untitled piece (most of Bontecou’s work is untitled) owned by the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago embodies the change in practice that Bontecou’s work underwent in the mid-1960s.

The Lee Bontecou exhibition at MoMA QNS (through September 24, 2004) hinges on a work from 1966. Hung in the middle of this chronologically installed show, the untitled piece (most of Bontecou’s work is untitled) owned by the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago embodies the change in practice that Bontecou’s work underwent in the mid-1960s.

Based on the wall-mounted armatures that she began using in the early 1960s, this piece bears a resemblance to her work from earlier in the decade—work that gained her national attention. This work is different, though. Its uses the welded steel, canvas, and wire of her earlier work. But in place of the saw blades and light-absorbing velveteen she had been using, Bontecou uses fiberglass. She attaches the pieces to the armature not with rough, knotted wire but with epoxy, changing the character of the work significantly. No longer does the work threaten to bite, cut, and poke its viewers. Its surface becomes smooth, almost asking to be stroked.

Gone as well are the large, dark openings that suck in, trap, and refuse to release light—the black hole of despair, the existential abyss. Instead, this work turns outward, focusing on surface. Bontecou even begins to include color. As if underscoring this transition from the threats of inner darkness to the affirmation of surface, Bontecou illuminates the work from within. Hidden behind the fiberglass panels, these unseen lights radiate through the materials, lighting the smooth surface, rather than sucking all surrounding light through a harsh, dangerous exterior into a central void.

Gone as well are the large, dark openings that suck in, trap, and refuse to release light—the black hole of despair, the existential abyss. Instead, this work turns outward, focusing on surface. Bontecou even begins to include color. As if underscoring this transition from the threats of inner darkness to the affirmation of surface, Bontecou illuminates the work from within. Hidden behind the fiberglass panels, these unseen lights radiate through the materials, lighting the smooth surface, rather than sucking all surrounding light through a harsh, dangerous exterior into a central void.

This piece splits Bontecou’s work into two periods. Prior work threatens, leading viewers to try to remember the date of their last tetanus shot. With this piece, her work moves from threat to affirmation, from hostility to transcendence, from an existential-influenced late modernism to a baroque-inspired post-modern.

The exhibition represents both before and after periods well, even though in its MoMA QNS incarnation the show is only half the size it was in previous venues. The work from the early 1960s, presented first in this chronological installation, is as powerful in mass as any admirer of Bontecou would expect. The curators have selected a set of works that shows the evolution of Bontecou’s signature form, from an early work that achieves its dark vortex effect with black mesh placed over the opening in the structure, to the more complex multi-orificed works using saw blades and ropes in conjunction with the recycled canvas that became her primary material during this period.

Works from the period of transition in the mid-1960s are also well represented. It’s possible in this installation to see Bontecou’s thinking change. We can see the transition in style occur over the period of a couple years as she begins to add color to her works, to work with materials other than canvas, to remove the sharp edges and blades, and to shrink the aperture around which her earlier works had been structured.

The show dutifully covers her period of experimentation in the late-1960s and 1970s (who didn’t experiment in one way or another during those years?) with vacuum-formed plastic. Her fish and flowers were not well received at the time. After these works were exhibited and panned by critics, Bontecou retreated to her Pennsylvania studio and did not show again publicly for many years. Today, however, they look good. They show the same attention to detail and obsessive fabrication that marked her work in the early 1960s. They also point the way toward the work that she has been doing over the last two decades.

This more recent work, not shown broadly in public before, overwhelms and amazes in its complexity, combination of materials, and originality. The work brings to mind baroque ornamentation, but it is truly unique.

Inspired by natural forms, these free-floating pieces do not so much bring to mind specific forms of life as do her fish and flowers as they cause sparks of recognition to ignite without allowing a fire of understanding to light. In these great constructions floating in space, we see reminders of small animal skulls, planets, leaves, and wings. But we never see any of these things themselves. What we see is Bontecou’s imagination at work, melding, transforming, reconfiguring familiar objects into constructs that also feel familiar but that overwhelm the visual cortex with their originality.

It is difficult to move back and forth between looking at the components of these works and looking at the whole because the individual objects—small pieces of porcelain, wire forms held together with wings of canvas—are so tightly integrated with all others in the piece. It’s like trying to pull apart aurally a Bach concerto. It’s possible to get pieces of the whole as they emerge for a moment in time, but it’s almost impossible to focus exclusively on a single instrumental line because of the strength of the integration of the whole. The complexity, ornamentation, joy, and integration of Bontecou’s recent work is every bit as moving and timeless as Bach’s music.

The one regret I have about the show’s installation is the amount of space that has been given to Bontecou’s drawing. Drawing has always been important to her process, but the drawing all feels very preparatory for the sculpture. Looking at the forms and ideas as they emerge in her drawing, and then seeing how much more lively, powerful, and moving they become when executed in three dimensions provides viewers with a tutorial in the artistic process. But the show should have presented less context (although Bontecou would probably disagree that her drawing is mere context and preparation for her sculpture) and more sculptural work.

This exhibition has done much already to revive Bontecou’s reputation and create new interest in her work. With it, Bontecou has emerged as one of the most original voices in contemporary American sculpture. It’s a place she should have held all along.

Thursday, August 05, 2004

NYFA Quarterly on the Mega-Exhibition

I tend toward love (more than toward hate) when it comes to the mega-exhibition of recent work. Sure these exhibitions can be tedious. But the love part I feel is tied to the fact that they usually introduce me to a few artists with whom I'm not familiar but whose work I begin to appreciate. With the Whitney Biennial this year it was Dario Robleto and Amy Cutler. With Open House it was Bill Scanga, Su-En Wong, and E.V. Day. I even found a couple gems recently at the Water Show in Red Hook.

Schwendener's article, however, tends to lean more toward the hate side of the love-hate dichotomy. That's OK. I can respect someone whose opinion differs from mine. And I can even recommend that people read her article. (So follow the link above and take a look at it.)

But after you've read her piece, please tell me what the heck she is doing in her penultimate paragraph. She can't really think she's doing Artists Space (an alternative gallery) a service by making an argument from analogy that turns them into the Al Qaeda of the contemporary New York art world. Can she?

Now, NYFA is a great organization, and NYFA Quarterly is a solid publication. But, my goodness. Just because someone has contributed to Artforum doesn't mean that her work doesn't need an editor to read it before it gets sent off to the printer.

Or, maybe, this situation should be used as a cautionary tale. Arts editors, take note. If a contributor lists Artforum in her author's bio, edit the piece especially closely.

Wednesday, August 04, 2004

Warm Up for the Fall Gallery Season

I'm still planning to post a review of the Lee Bontecou exhibition at MoMA QNS, but I've been on the road and haven't been able to carve out the time to write it yet. It's coming soon. I promise.

In the interim, here's a little something to get you all warmed up for two solid weeks of gallery openings come September. Practice now so that you're not the ugly gallery hopper out on the sidewalk in front of that week's big opening reception sleeping off one too many glasses of chardonnay.

Tuesday, August 03, 2004

America's Big Nothing at the Venice Biennale

It turns out that the NEA doesn't want to be involved in the decision making process anymore, funding sources have dried up, the Guggenheim isn't interested in opening another branch (what's that?), and so on and so forth. So, bottom line, unless the situation changes quickly there may not be an American representative in the show.

The one artist mentioned specifically as a candidate is Ed Ruscha. Would it be better to have Ed Ruscha as the U.S. representative or to submit nothing?

Don't make me answer that question.

Monday, August 02, 2004

Five Simple Rules for Talking about Art

Yesterday's group was small, but it included an adorable nine-month-old girl who crawled around the floor while her mother listened to me speak. The infant stole the show. Neither Ana Mendieta's work (not even the work where she gets naked) nor I (I remained fully clothed) could compete successfully with the baby for the audience's attention.

With groups being a third their usual size this summer, I've been able to do more discussing and less lecturing than I typically do. I guess this makes me seem more approachable because over the last few weeks I've received some generous compliments from guests during and after my talks.

Feeling bolstered by the kudos and looking to improve the quality of arts interpretation world wide (okay, so I still find it novel and amusing that this blog is being read in ten time zones), I thought I would share some secrets I use when I prepare a gallery talk.

Here are my five rules for talking about art that's hanging in a gallery. Each rule has a Do component and a corresponding Don't component.

- Do develop an overall theme or narrative to structure what you are going to say. Don't overwork the theme while you talk about individual works. Instead, highlight the theme when making transitions between works (see Rule 5).

- Do select works to talk about strategically, ensuring that they allow you to develop your theme. Don't try to talk about everything on display. Limit yourself to a few select pieces and talk about them in greater detail.

- Do make a point of actually looking at (and getting your audience to look at) each work as you speak about it. Take advantage of the fact that you're in the presence of the piece to get your audience to look deeply at some detail. Don't get so lost in what you think is important about the work that you forget to show your audience how to look at what's in front of them.

- Do inform your discussion with biography, history, and critical theory. Don't, though, reduce the work to an illustration of biography, historical context, or theory.

- Do develop and use transitions to move your group from one object to the next. Don't ever move a group between works with, "And now let's go to the next gallery."

One of the best compliments I ever received on a gallery talk came from a visitor who approached me at the end of a presentation and said, "That was so interesting. It was just like reading a novel."

I now use that compliment as a touchstone for evaluating a talk before I start giving it. If it doesn't feel like a novel--with a theme, a plot line based on discrete components linked together with transitions, interesting visual description, and rich contextual support--I know I need to do more work on it before I roll it out.

Update: See this post for rule number 6.

Sunday, August 01, 2004

Lee Bontecou Arrives in Queens

The Lee Bontecou exhibition opened at MoMA QNS on Friday. In certain respects, this show has reminded me of a major snow storm. As it has moved east across the country, it has picked up additional steam and has received increasing media coverage. By the time it hit the New York area this weekend, the art viewing public was ready for something big.

The Lee Bontecou exhibition opened at MoMA QNS on Friday. In certain respects, this show has reminded me of a major snow storm. As it has moved east across the country, it has picked up additional steam and has received increasing media coverage. By the time it hit the New York area this weekend, the art viewing public was ready for something big.

I've been waiting for ages to see this show. I was actually in downtown Chicago for a day last April while the exhibition was at the Museum of Contemporary Art. Unfortunately, it was a Monday and the MCA was closed. I wandered around the perimeter of the building, my museum credential in hand, hoping to beg my way in a back door to get a quick glimpse of the show. I didn't have any luck.

I finally had the chance to see it yesterday at MoMA. I will post something more in-depth on the exhibition later this week, work and travel allowing. But in the meantime don't wait. Go see it for yourself early in its run because you'll want to have time to go back to see it again. And again. And, maybe, again.