Saturday, August 07, 2004

Lee Bontecou's Contemporary Baroque

The Lee Bontecou exhibition at MoMA QNS (through September 24, 2004) hinges on a work from 1966. Hung in the middle of this chronologically installed show, the untitled piece (most of Bontecou’s work is untitled) owned by the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago embodies the change in practice that Bontecou’s work underwent in the mid-1960s.

The Lee Bontecou exhibition at MoMA QNS (through September 24, 2004) hinges on a work from 1966. Hung in the middle of this chronologically installed show, the untitled piece (most of Bontecou’s work is untitled) owned by the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago embodies the change in practice that Bontecou’s work underwent in the mid-1960s.

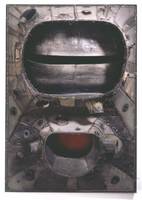

Based on the wall-mounted armatures that she began using in the early 1960s, this piece bears a resemblance to her work from earlier in the decade—work that gained her national attention. This work is different, though. Its uses the welded steel, canvas, and wire of her earlier work. But in place of the saw blades and light-absorbing velveteen she had been using, Bontecou uses fiberglass. She attaches the pieces to the armature not with rough, knotted wire but with epoxy, changing the character of the work significantly. No longer does the work threaten to bite, cut, and poke its viewers. Its surface becomes smooth, almost asking to be stroked.

Gone as well are the large, dark openings that suck in, trap, and refuse to release light—the black hole of despair, the existential abyss. Instead, this work turns outward, focusing on surface. Bontecou even begins to include color. As if underscoring this transition from the threats of inner darkness to the affirmation of surface, Bontecou illuminates the work from within. Hidden behind the fiberglass panels, these unseen lights radiate through the materials, lighting the smooth surface, rather than sucking all surrounding light through a harsh, dangerous exterior into a central void.

Gone as well are the large, dark openings that suck in, trap, and refuse to release light—the black hole of despair, the existential abyss. Instead, this work turns outward, focusing on surface. Bontecou even begins to include color. As if underscoring this transition from the threats of inner darkness to the affirmation of surface, Bontecou illuminates the work from within. Hidden behind the fiberglass panels, these unseen lights radiate through the materials, lighting the smooth surface, rather than sucking all surrounding light through a harsh, dangerous exterior into a central void.

This piece splits Bontecou’s work into two periods. Prior work threatens, leading viewers to try to remember the date of their last tetanus shot. With this piece, her work moves from threat to affirmation, from hostility to transcendence, from an existential-influenced late modernism to a baroque-inspired post-modern.

The exhibition represents both before and after periods well, even though in its MoMA QNS incarnation the show is only half the size it was in previous venues. The work from the early 1960s, presented first in this chronological installation, is as powerful in mass as any admirer of Bontecou would expect. The curators have selected a set of works that shows the evolution of Bontecou’s signature form, from an early work that achieves its dark vortex effect with black mesh placed over the opening in the structure, to the more complex multi-orificed works using saw blades and ropes in conjunction with the recycled canvas that became her primary material during this period.

Works from the period of transition in the mid-1960s are also well represented. It’s possible in this installation to see Bontecou’s thinking change. We can see the transition in style occur over the period of a couple years as she begins to add color to her works, to work with materials other than canvas, to remove the sharp edges and blades, and to shrink the aperture around which her earlier works had been structured.

The show dutifully covers her period of experimentation in the late-1960s and 1970s (who didn’t experiment in one way or another during those years?) with vacuum-formed plastic. Her fish and flowers were not well received at the time. After these works were exhibited and panned by critics, Bontecou retreated to her Pennsylvania studio and did not show again publicly for many years. Today, however, they look good. They show the same attention to detail and obsessive fabrication that marked her work in the early 1960s. They also point the way toward the work that she has been doing over the last two decades.

This more recent work, not shown broadly in public before, overwhelms and amazes in its complexity, combination of materials, and originality. The work brings to mind baroque ornamentation, but it is truly unique.

Inspired by natural forms, these free-floating pieces do not so much bring to mind specific forms of life as do her fish and flowers as they cause sparks of recognition to ignite without allowing a fire of understanding to light. In these great constructions floating in space, we see reminders of small animal skulls, planets, leaves, and wings. But we never see any of these things themselves. What we see is Bontecou’s imagination at work, melding, transforming, reconfiguring familiar objects into constructs that also feel familiar but that overwhelm the visual cortex with their originality.

It is difficult to move back and forth between looking at the components of these works and looking at the whole because the individual objects—small pieces of porcelain, wire forms held together with wings of canvas—are so tightly integrated with all others in the piece. It’s like trying to pull apart aurally a Bach concerto. It’s possible to get pieces of the whole as they emerge for a moment in time, but it’s almost impossible to focus exclusively on a single instrumental line because of the strength of the integration of the whole. The complexity, ornamentation, joy, and integration of Bontecou’s recent work is every bit as moving and timeless as Bach’s music.

The one regret I have about the show’s installation is the amount of space that has been given to Bontecou’s drawing. Drawing has always been important to her process, but the drawing all feels very preparatory for the sculpture. Looking at the forms and ideas as they emerge in her drawing, and then seeing how much more lively, powerful, and moving they become when executed in three dimensions provides viewers with a tutorial in the artistic process. But the show should have presented less context (although Bontecou would probably disagree that her drawing is mere context and preparation for her sculpture) and more sculptural work.

This exhibition has done much already to revive Bontecou’s reputation and create new interest in her work. With it, Bontecou has emerged as one of the most original voices in contemporary American sculpture. It’s a place she should have held all along.