Tuesday, December 27, 2005

Spectacle, But Not Much Else, in the Turbine Hall

The scale of the space almost ensures that anything commissioned for it will partake of spectacle. Anish Kapoor’s 2002 installation Marsyas and Olafur Eliasson’s The Weather Project from 2003 certainly did. Bruce Nauman’s soundscape Raw Materials from last year, on the other hand, did what Nauman does so well by taking a contradictory stance—negating the assumption of visual spectacle to leave viewers with a pure audio experience.

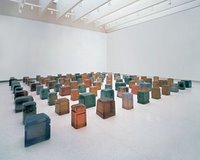

Rachel Whiteread’s current installation in the space, Embankment (at right), achieves a moderate level of success. The element of spectacle is at play in the work to a degree sufficient to make the installation interesting. But Whiteread’s concept and use of materials do not rise to a level that would make the work truly memorable.

Rachel Whiteread’s current installation in the space, Embankment (at right), achieves a moderate level of success. The element of spectacle is at play in the work to a degree sufficient to make the installation interesting. But Whiteread’s concept and use of materials do not rise to a level that would make the work truly memorable.Whiteread has filled the Hall with casts of boxes—thousands of them. The installation has the requisite conceptual framework for a major piece of contemporary art. Whiteread has spoken about finding inspiration for the installation in an old box that once belonged to her mother. She layers on top of this personal memory a pop cultural reference by talking about the impression made on her by the final scene in Raiders of the Lost Ark where the Ark of the Covenant is boxed up and placed in a generic warehouse somewhere. She also talks about the process of casting and making a negative and then a positive image of her mother’s old box and the philosophical implications thereof.

It’s all the right talk for a major commission like this, but none of it really matters. The power of the piece comes from the massive assemblage of items Whiteread has created. It doesn’t matter that the stacks she has created are made of casts of casts of objects. It doesn’t matter that the items cast were boxes. The work is all about the stacking—the massing of objects—and the viewer’s experience of walking through them.

If you enter the building from the Thames side, you come in one level above the installation and have the opportunity to view it from a balcony. Seeing it from this vantage point provides a completely different experience than going down to the ground floor and walking through the labyrinth that the Whiteread has made.

When you walk among the piles (at right), you begin to feel vulnerable. Your body, in comparison to these massive towering piles, feels small. You feel a sense of endangerment as you pass between the stacks.

When you walk among the piles (at right), you begin to feel vulnerable. Your body, in comparison to these massive towering piles, feels small. You feel a sense of endangerment as you pass between the stacks.The piece, in this way, partakes of the what Michael Fried called the theatrical nature of minimalism. It does so, though, to a much greater degree than any piece of minimalist work I know. In a way, walking through this installation feels like walking through one of Richard Serra’s torqued ellipse. You feel like your life could be threatened at any moment by a strong gust of wind or a small tremor of the ground.

Whiteread’s installations takes a shortcut this way. The piece is all show (a great experience) but no tell as it lacks an instigating concept as interesting as the “wow!” experience of walking through the piece. She has tried to provide one, but the concept is weak. It can’t stand up to the impression made by the objects.

Seeing Whiteread’s installation in the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall brought back to mind her piece that was installed in the Guggenheim’s rotunda as part of the Singular Forms (Sometimes Repeated) show in 2004. This untitled piece (at left), 100 colored resin casts of the space beneath chairs, is much more subtle and meditative than the Turbine Hall installation. It doesn’t create spectacle in any manner. But to me it it’s the more interesting of the two works.

Seeing Whiteread’s installation in the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall brought back to mind her piece that was installed in the Guggenheim’s rotunda as part of the Singular Forms (Sometimes Repeated) show in 2004. This untitled piece (at left), 100 colored resin casts of the space beneath chairs, is much more subtle and meditative than the Turbine Hall installation. It doesn’t create spectacle in any manner. But to me it it’s the more interesting of the two works.The meditative feel of the untitled work forces contemplation of the concept in a way that the Turbine Hall installation doesn’t, and the colored resin used for the casts provides more visual interest. The work stands on its own—it speaks for itself—in a way that the Turbine Hall installation doesn’t. The piece doesn’t rely on the shock of spectacle to make its impression.

For this more recent commission, Whiteread has taken the easy way out by falling back on the crutch of spectacle that the massive space provides to her, and she allows spectacle to carry the work rather than creating a piece that uses the space in an interesting way that integrates with and supports the concept and materials she has chosen for the installation.

That said, I would still jump at the chance to spend a half hour walking among Whiteread's boxes if the opportunity presented itself again.

Rachel Whiteread’s Embankment is on display in the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall through April 2, 2006.

Wednesday, December 21, 2005

Martin Parr on the Street in Cambridge

Just about everywhere you look in New York, construction barriers become a magnet for posters. The first poster gets pasted up over the standard "Post No Bills" stencil, and from then on the site is free game for anyone with paper and some wheat paste. If the site is below Houston St., there's a chance that what goes up overnight will be interesting street art. If the site is above 23rd St., it's probably going to be advertising (if it's not advertising masquerading as street art).

Just about everywhere you look in New York, construction barriers become a magnet for posters. The first poster gets pasted up over the standard "Post No Bills" stencil, and from then on the site is free game for anyone with paper and some wheat paste. If the site is below Houston St., there's a chance that what goes up overnight will be interesting street art. If the site is above 23rd St., it's probably going to be advertising (if it's not advertising masquerading as street art).When I stopped in Cambridge last week, I came across an interesting approach to institutionalizing the activity of posting bills on construction barricades.

A large building is now going up on a heavily trafficked street (above left) in the center of the city. For some reason (interest in art? civic pride? an attempt to keep graffiti and advertising off their barricade?), the developers have launched an interesting project by commissioning native Brit and Magnum photographer Martin Parr to take "portraits" of the city during the three years that this site will be under development. Over that period they will continually post Parr's work on the fence surrounding the job site.

The project isn't as easy as one might guess for a photographer like Parr who specializes in documenting the real (and unaesthetic) look of contemporary suburban life. Parr writes about the project:

I had not been to Cambridge for many years and was eagerly anticipating rediscovering the city. I was almost overwhelmed by how beautiful the city was and this is almost a disadvantage for a photographer. Everywhere you look you are in danger of photographing a cliche that could become a picture post card.

The first several photographs posted (at right) do a fine job of avoiding cliche as they force city residents and visitors to stop for a moment and contemplate scenes that don't present the typical view of this picturesque city.

The first several photographs posted (at right) do a fine job of avoiding cliche as they force city residents and visitors to stop for a moment and contemplate scenes that don't present the typical view of this picturesque city.In upcoming months Parr will continue to visit and document the city, showing new work at this site until the building is complete and the barricades come down in 2008.

Related: Martin Parr's "Mobile Phones" project. (Warning: turn your speakers down before clicking.)

Monday, December 19, 2005

Seen and Not Seen

While part of me wishes I had been able to spend more than a few hours at home over the weekend, I was able to squeeze in viewing of a few shows in England during the time away. Work commitments permitting, I'll have something later this week on the Turner Prize finalist show at the Tate, on the Rachel Whiteread installation in the Turbine Hall at Tate Modern, and on an interesting approach to institutionalizing street art that I came across in Cambridge.

I won't, though, have something on the new installation of the Tate Modern's permanent collection--half of which opens tomorrow--as I had hoped. But that's not for lack of trying. It seems the Tate's press office doesn't quite have this whole blog thing figured out yet. Some museum press offices (the Carnegie, the Whitney) get it. Others (MoMA, the Tate) don't.

Sunday, December 11, 2005

On Hiatus This Week

Thursday, December 08, 2005

Elsewhere Today

- MAN has a good take on Fisk University's deaccessioning of an O'Keeffe and a Hartley. While I'm never in favor, philosophically, of the practice, I'm much more open than Tyler is to using it strategically. This seems to be a case where it is justified. I'm glad to see that Tyler recognizes the difference between this instance and other recent, high profile cases.

- Interesting thoughts on The View from the Edge of the Universe on artists and their self-defined programs for making art or the "beautiful calculation." Robust conceptual practice or a strategy of building a whole career for a one hit wonder? You decide.

Tuesday, December 06, 2005

Turner (Yawn) Prize Winner Announced

The only reason I know this is that I was in Montreal this morning (Anyone know exactly how cold it is in Montreal right now? It's damn cold.) and I happened to be browsing through The Globe and Mail over breakfast.

Simon Starling has won this year's prize.

As Canada's paper of record, The Globe and Mail did a fine job of not denigrating his work too directly. But the backhanded analysis was all too clear. The story was told with one large photo and a photo caption (that isn't available on line) which I should have saved but didn't. If memory serves me correctly, it went something like this:

Artist Simon Starling has been awarded this year's Turner Prize. Starling is pictured with his work Shedboatshed. For this work Starling disassembled a shed, turned it into a boat, and then rebuilt it as a shed.Um, sounds trés compelling, right?

OK, so I shouldn't judge until I've seen the work. I didn't think much of last year's Turner Prize nominees, and I don't think I'll think much more of this year's work based on what I've seen on line. But I'll give the work the benefit of the doubt. I've managed to arrange my travel schedule so that I'll get to see the show of nominees' work at the Tate next weekend. I'll have more to say about it then, I'm sure.

Wednesday, November 30, 2005

Art, American Style

- The Whitney has announced the line up for the 2006 Biennial. For the first time, the exhibition has received a subtitle, "Day for Night." According to curator Chrissie Iles, the exhibition "explores the artifice of American culture in what could be described as a pre-Enlightenment moment, in which culture is preoccupied with the irrational, the religious, the dark, the erotic, and the violent, filtered through a sense of flawed beauty. This reflective, restless mood is not unique to the United States; its presence across both America and Europe suggests a shift in the accepted values that have formed the basis of 20th-century Western culture." Philippe Vergne of the Walker has co-curated the show. A list of artists selected for the exhibition is available via the link above.

- The Smithsonian American Art Museum has launched a new blog, Eye Level. Written by Kriston Capps of Grammar.police fame, the site looks like it's going to quickly become a daily read and the model for what an institution-affiliated blog can do.

- And, speaking of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, I recently came across its fabulous Ask Joan of Art service. (OK, the service is great but the name may leave a little to be desired.) Through this website, Smithsonian researchers offer a no cost research service for questions related to American art and artists.

Tuesday, November 29, 2005

Why I’m Not Going to Miami

For some reason, people have a hard time believing that I don’t make the annual pilgrimage to Miami for Art Basel Miami Beach. The fact of the matter is that I just don’t have a lot of interest in spending the weekend that deep in the belly of the art market beast.

For some reason, people have a hard time believing that I don’t make the annual pilgrimage to Miami for Art Basel Miami Beach. The fact of the matter is that I just don’t have a lot of interest in spending the weekend that deep in the belly of the art market beast.I’m more into the art than into the art scene. I get the sense that early December in Miami has rapidly become more about the scene than about the art.

But there is a host of secondary reasons why I don’t make the trip. Here’s a partial list:

- I like having Chelsea all to myself for one weekend a year.

- ABMB is not that interested in credentialing bloggers, so why bother giving the fair the publicity. (Side note to any arts publicists not yet convinced that blogs are as important as traditional print media: Back in the day, I used to work on a small but credible print publication. This site gets more than thirty-five times more unique visits each month than that magazine had subscribers.)

- NetJets gets all maxed out during this week and can’t provide me with a plane to get into Miami at exactly the time I want to go (um, as if...).

- If a huge crowd of people is all looking in the same direction, I tend to think that there’s probably something more interesting going on in another direction where nobody else is looking.

- I do so much travel for work that I’ve developed a philosophical aversion to paying my own way to go anywhere; I haven’t yet found anyone willing to cover my expenses for a trip to ABMB.

- Speaking of work, I can’t afford the time off right now.

- Not speaking of work, I really can’t stand the feeling of having sand stuck in a wet bathing suit while I’m looking at art.

- Finally, I’ve become so fed up with it that I’m sort of boycotting the art market these days. My last several purchases have been commissions directly from artists. I find this a much, much more rewarding way to purchase art than buying from gallery booths at fairs.

Sunday, November 27, 2005

It's Good to be the Wizard

Being the Wizard means never having to say you're sorry. Even when you run over things with that chair of yours.

Being the Wizard means never having to say you're sorry. Even when you run over things with that chair of yours.Like when you flatten Dorothy's little dog Toto in that wacky Annie Leibovitz multi-page, artist-filled Wizard of Oz spread in the December Vogue. (See the Wizard crunching his furry victim at right and the penultimate item here for a full description of the spread.)

Or like when you run into the back of Mrs. FtF's seat and then roll over the kid's diaper bag at Sarabeth's at the Whitney on the Friday after Thanksgiving.

We love you Chuck. We really do. But we would love you even more if you wheeled around a bit more courteously.

Wednesday, November 23, 2005

What Do You Think?

Tuesday, November 22, 2005

What Can You Do with All That Sublimation?

I'm supposed to be giving gallery talks on the Richard Tuttle exhibition at the Whitney, but I've been on the road so much lately that I haven't even seen the show yet. (I figured out yesterday that excluding time spent at airports and in cabs, I've had a grand total of 24 hours and 45 minutes in New York over the last two and a half weeks.)

I'm supposed to be giving gallery talks on the Richard Tuttle exhibition at the Whitney, but I've been on the road so much lately that I haven't even seen the show yet. (I figured out yesterday that excluding time spent at airports and in cabs, I've had a grand total of 24 hours and 45 minutes in New York over the last two and a half weeks.)I have, though, been doing some reading on Tuttle in preparation for the show. One of the things that has struck me is Tuttle's continual emphasis on not asserting meaning through his work. Here's a quote from Tuttle that appears in the catalogue for season 3 of Art:21:

There's a division left over from the twentieth century where certain people might think that art is something that is made outside of any personal expression (Josef Albers or the Bauhaus), that it's really coolly detached. And then there's the other side, where art is full of personal expression. I guess the personal expression side is great, but then you can get an art which is just an expression of some twisted personal idiosyncrasy. In order to get over those polarities between no personal expression and personal expression, the only possible expression is one of some sort of sublimation.I'm curious to see how that sublimation takes shape in the work selected for the show and in the gallery installations. And I'm really curious about how the heck I'm going to put together a coherent talk about work that is so purposely indirect.

Monday, November 21, 2005

Why Do I Bother?

Actually, no art writers did. None. Not that Carol Vogel is known for deep, investigative journalism, but you would think that the list makers would have given her a little love here for the way New York museums bow, scrape, and hold back info to give her those press-release friendly exclusives.

Thursday, November 17, 2005

Mistakes Were Made

Charlie Finch visited the Columbia MFA studios recently and returned with an interesting report about how the young painters there are dealing with the pressures of not having enough quiet time to focus on their work.

Paul Schimmel made a similar point last weekend at the panel discussion I attended. Students, he said, are working to make gallery shows, not art. “If you can’t do something awful when you’re a student,” he asked rhetorically, “when can you?”

At the National Museum of Catalunian Art on Sunday, I happened to stumble across a show of video work by eight recent Yale graduates. (The screening was part of the Loop Festival of video art running this month in Barcelona.) I’m happy to report that the video division of this venerable art program hasn’t caved one inch to market pressure. It’s still turning ’em out old school style in a way that would make Schimmel happy. All eight of these Yale grads, I have to say, have made truly awful things.

I don’t mean to slag the artists whose work was included in the screening, so I won't name names (other than that of professor John Pilson who selected the work). But, man, the pieces chosen to showcase Yale at this international event give student work the world over a bad name. And Yale a very bad name.

I can’t help but feel sorry for these recent grads. I mean, imagining paying Ivy League rates for a professional training program that only enables you to produce output like this. Now I understand where the term "starving artist" comes from. Having massive loans to repay and making work that no one would ever be interested in buying (let alone actually watching--even once) must make it pretty darn hard to put food on the table.

Tuesday, November 15, 2005

Groaners, All of Them

How many curators does it take to change a light bulb?

That’s not a curatorial task. You’ll have to call maintenance.

How many educators does it take to change a light bulb?

That’s a very important question and many artists have addressed it, each in his or her own individual way, since the turn of the last century.

How many development staff does it take to change a light bulb?

Just one. But if we had the funding, we could put two or three people on it, ensuring a much higher quality outcome. Would you be interested in supporting that effort?

How many publications employees does it take to change a light bulb?

Wait a minute. Are you sure you have all the permissions nailed down to do that?

How many communications staff does it take to change a light bulb?

I’m not sure. Let me follow up on that. Can I give you a call back later today?

How many security officers does it take to change a light bulb?

Excuse me. Stand back from that bulb, please.

How many art handlers does it take to change a light bulb?

That’s not really in the job description, but what the hell. Where’s the fresh bulb?

Saturday, November 12, 2005

One the Kid Won't Be Seeing

Now I can't decide who's worse - moms who force their kids to potty train at 6 months, or dads who make their 8-month olds watch films about self-mutilating hookers.Well, when you put it that way....

So I'm glad to say that one of the shows I saw today was one that I saw sans la fille. Günter Brus: Nervous Stillness on the Horizon at MACBA is a career retrospective of work by the Viennese Actionist. One interesting outcome of having so much of Brus's work from the 1960s and '70s assembled is the ability it gives to see the lines of influence running from him to American artists such as Paul McCarthy and Ana Mendieta who emerged during those years.

So I'm glad to say that one of the shows I saw today was one that I saw sans la fille. Günter Brus: Nervous Stillness on the Horizon at MACBA is a career retrospective of work by the Viennese Actionist. One interesting outcome of having so much of Brus's work from the 1960s and '70s assembled is the ability it gives to see the lines of influence running from him to American artists such as Paul McCarthy and Ana Mendieta who emerged during those years.But, whoa. What a tough show to look at. Take, for example, this description (lifted from the gallery brochure) of Brus's 1970 performance piece Zerreissprobe (Breaking Test) which is documented in the exhibition in stills and on film:

In it Brus, totally shaved, injured himself in the style of the historical and pictorial tradition of the martyr. The action focused on the vulnerability of the individual, pain and "pure" madness, and marked the climactic and final moment of the period.That, I think, pretty much describes the ethos of the whole show. Brus's work makes McCarthy's gross out nastiness stuff look like the child's play it really is. Oh, and I almost forgot. There's another film in the exhibition showing Brus wetting himself. Nice, I suppose, if you're into that kind of stuff.

Thursday, November 10, 2005

Dirty Dealing?

The panel, part of a larger conference on museum acquisitions and deaccessioning organized by the American Federation of Arts, featured Raymond Learsy (collector and Whitney Museum trustee), the artist Jeff Koons, Paul Schimmel (chief curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles), and gallerist Marianne Boesky.

Insights by panel members ranged from the obvious (Learsy: the art market isn’t the insular little world it used to be) to the sound (Schimmel: explore more affordable work by underappreciated, mid-career artists) to the surreal (Koons: “This machine, this market, is showing how people love each other.”)

What intrigued me most, though, was a statement that Marianne Boesky let slip.

Boesky has made no secret about the process she uses for determining who gets to buy work by her very in-demand artists: identify a museum where she wants to place a work, find a collector affiliated with the organization, sell the collector a piece with the requirement that it be given as a partial gift to the institution.

Reiterating these well documented points for the museum staffers last weekend, Boesky added, “I work for the artist. We pick and choose who gets access [to work] for strategic reasons, for careers to grow,” adding generously that Whitney trustee Learsy could walk into her gallery and buy anything he wanted.

Not everyone is so fortunate. Boesky clearly has scorn for the new hedge fund collectors who think they can buy access to work by desirable artists. “Waiting lists are not linear things,” she said. “It’s not who gets there first.” Or who arrives with the most money.

None of this is news—surprising as it might be to those who think markets do, or should, operate efficiently. A Google search on Boesky’s name turns up several articles that quote her describing this strategy. What was new, though, was a piece of information that Boesky dropped almost in passing.

She mentioned that a few years ago Takashi Murakami paintings were selling at galleries that represent him for $60,000 while they were fetching $600,000 at auction. Murakami’s dealers from around the world, Boesky told the audience, got together to “do something” in response to this large price differential. (I assumed she was implying that they decided to either raise Murakami’s primary market prices or influence secondary market pricing, but she did not say this directly.)

That’s a fairly innocuous comment taken in the context of the whole of what Boesky does to manage the market for her artists’ works. But it’s one that may indicate that her market practices have crossed a line.

The U.S. Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division makes available on its website a pamphlet entitled “Antitrust Enforcement and the Consumer.” The purpose of the document is to help the general public identify antitrust activities. It contains the following advice:

That bullet point (the first of several which I haven’t quoted) summarizes many aspects of Boesky’s market practices—especially the practice of meeting with competing sellers of the same product to “do something” about how that product is priced (if that is indeed what the discussion was about).How Can You Know if the Antitrust Laws Are Being Violated?

If any person knows or suspects that competitors, suppliers or even an employer are violating the antitrust laws, that person should alert the antitrust authorities so that they can determine whether to investigate.

Price-fixing, bid-rigging and customer-allocation conspiracies are most likely to occur where there are relatively few sellers who have to get together to agree. The larger the group of sellers, the more difficult it is to come to an agreement and enforce it.Keep an eye out for telltale signs, including, for example:

- any evidence that two or more competing sellers of similar products have agreed to price their products a certain way, to sell only a certain amount of their product or to sell only in certain areas or to certain customers

I’m not an attorney, and I don’t claim detailed knowledge of U.S. antitrust law. But as a consumer of products offered for sale on the art market, it seems to me that antitrust authorities would be justified in investigating whether Boesky has violated the law.

Boesky is a very bright woman and, I believe, an attorney herself. She has also had ample, first-hand exposure to the penalties faced by individuals who do not play by the market’s rules. (Her father, Ivan Boesky, famously plead guilty to involvement in a massive insider trading scandal in the mid-1980s. He eventually served jail time and paid a whopping $100M fine.)

All this would lead me to believe that Marianne Boesky would want to stay on the right side of the law as she makes markets in the work of the artists she represents. But listening to her talk about her activities makes me wonder if she is doing otherwise.

Related: Felix Salmon from last March on the irrationality of the art market.

Wednesday, November 09, 2005

Getting His Show on the Road

The blogosphere's favorite institutional rabble-rouser, Homeless Museum director Filip Noterdaeme, will be setting up an admission-free alternate MoMA in front of $20 MoMA on November 21 to mark the one year anniversary of the museum's reopening. His museum in a suitcase (dubbed MoMA HMLSS) contains over 100 miniaturized pieces from the full-sized MoMA's collection.

The blogosphere's favorite institutional rabble-rouser, Homeless Museum director Filip Noterdaeme, will be setting up an admission-free alternate MoMA in front of $20 MoMA on November 21 to mark the one year anniversary of the museum's reopening. His museum in a suitcase (dubbed MoMA HMLSS) contains over 100 miniaturized pieces from the full-sized MoMA's collection.A major benefit of housing a museum in a suitcase? It travels well. MoMA HMLSS has already been on display in France, Belgium, and Kansas City, MO. The next stop after Manhattan is Madrid.

Tuesday, November 08, 2005

On the Universal in Art, or Another Post about Crying

All well and good in theory, but I had an experience last weekend that has caused me to start questioning this belief.

Saturday afternoon the kid and I stopped by Gladstone Gallery to see the new Shirin Neshat video, Zarin. The kid is always happy to see art and, believe it or not, at eight months she’s even starting to express a preference for video. Most of the time she’s got an attention span measured in seconds. But put her in front of a large screen of moving light and she’s transfixed. At the Whitney recently she actually sat through the whole 30 minute Robert Smithson film on the making of Spiral Jetty. Given that, I figured we would be good for 15 minutes of Neshat.

When we walked in, the gallery was packed. All the benches were full, so we made our way to the front of the room to sit down on the floor. I took her out of her carrier and set her on the floor next to me. She immediately turned to face the screen and started watching.

We arrived just at the point in the narrative where Zarin, the emotionally disturbed title character, enters a public bath. Everything was fine with us until Zarin’s covering fell away and her washing crossed the line into self-mutilation. (A still from this scene is at right.) All of a sudden, out of nowhere, the kid started wailing. She wouldn’t stop. I had to walk her out of the gallery to calm her down.

We arrived just at the point in the narrative where Zarin, the emotionally disturbed title character, enters a public bath. Everything was fine with us until Zarin’s covering fell away and her washing crossed the line into self-mutilation. (A still from this scene is at right.) All of a sudden, out of nowhere, the kid started wailing. She wouldn’t stop. I had to walk her out of the gallery to calm her down.I found the point at which she became upset to be curious. It’s exactly the same point at which Edward Winkleman reported that he and others watching the film began sobbing.

Winkleman situates his emotional reaction to this scene in a cultural understanding of the mores that it transgresses:

Now I know just enough about Muslim culture (but not enough about Persian subtlties) to be rather wobbly informed about this, but it's my understanding that total adult nudity is highly inappropriate in the public baths. It certainly is for men, and so this scene was particularly confusing and thereby even more powerful for me.My kid couldn’t possibly know this, yet she reacted in the same way at exactly the same point in the film.

What the other 15 or so folks watching at the same time I was thought it symbolized, I'll never know, but I do know I was not the only one sobbing at this point in the film. (Sniffles carry.)

This makes me wonder if there isn’t something hard coded into humans, something existing deep in the preconscious portion of our brains, that recognizes when certain, basic assumptions about human behavior are challenged.

When Zarin begins scrubbing her skin raw, Neshat shows a person violating something fundamental to human nature—a will to self-preservation, a preference for pleasure over pain.

Witnessing these assumptions being transgressed, I am starting to think, creates an involuntary response in any viewer. Distributing feelings of shock, horror, pity, and perhaps fear arise unbidden. It’s as if we can’t help but feel these emotions if we are human. It’s instinctual.

My daughter’s reaction to Neshat’s work has to have been made at the level of instinct. She’s too young for it to have been anything else. She responded by vocalizing the distress that the video made her feel. I didn’t cry during the scene, but that doesn’t mean that I too didn’t have a strong emotional response. Perhaps it was my ability to dissociate representation from reality (something she is not yet capable of doing) that allowed me to retain my composure.

Could it be that in this work Neshat goes to a place in every viewer’s biological makeup and flips a switch causing an involuntary emotional response to occur? If that is indeed what happens here, that fact should be enough to open up for discussion again the notion that art can carry a universal meaning.

Monday, November 07, 2005

Teaser

Thursday, November 03, 2005

Excuses, Whining, and Moaning

I'm heading back home today, and I have a full weekend of art-type stuff planned (gallery walk with a museum group, auction previews, panel discussion on collecting in the current market environment). So maybe, if time and other paying commitments allow, there will be a few notes of interest showing up here next week.

Tuesday, November 01, 2005

Where the Power REALLY Lies

We wander for a while, looking at the new shows. Mrs. FtF (usually pretty charitable in her opinions) says of one group exhibition, "This is horrible." She's right. It is.

By 4:30 we've seen enough. But I want to see the Turrell. So we sit down in the hallway outside the room to wait. Soon a crowd starts to form. At 4:45 it's me, the wife and kid, and a group of 20 German tourists. I can understand exactly three words of what they are saying among themselves: "Turrell," "Roden," and "Crater."

By 4:30 we've seen enough. But I want to see the Turrell. So we sit down in the hallway outside the room to wait. Soon a crowd starts to form. At 4:45 it's me, the wife and kid, and a group of 20 German tourists. I can understand exactly three words of what they are saying among themselves: "Turrell," "Roden," and "Crater."At 4:55 the door still isn't open. The Germans are getting restless. One of them starts making paper hats for the kid out of the floor plans they are all carrying. Security staff members are pacing the hallway. Mrs. FtF overhears them discussing the problem. They've lost the key to the door. Brilliant. You put a major piece of contemporary art behind a locked door, and you don't keep a spare key around?

I'm about ready to pack it in when along comes one of the art handlers. He's been installing a show in another gallery on the floor. He sizes up the situation, pulls a Five-in-One painter's tool out of his pocket, sticks it between the door and the jamb, gives a little pull, and pops the door open for us.

Now I know who really holds the keys to the art world kingdom. It's that anonymous guy who nobody trusts with a key but who's always got the right tool in his back pocket.

Saturday, October 29, 2005

Cautionary Tales

- If an artist offers to swap you new work for old, do it.

- If the Guggenheim asks you to lend it work, don't do it (via).

- If you're thinking about inviting that OC Art Blog guy to your Halloween party, think again. Ewww.

Tuesday, October 25, 2005

Those Weak, Weepy Bloggers

First, I admit to getting all teared up by Janet Cardiff's Forty-Part Motet, and then Edward admits to the same while watching the new Shirin Neshat video.

Start by reading his excellent piece. Then select one or more options from the following list.

I think that all these sissy-boy art bloggers ought to toughen up and:

- Spend their free time watching football instead of hanging out in museums and galleries

- Quit ordering cosmos and start drinking Bud

- Realize that everyone belches; go ahead and do it with gusto when the need arises

- Accept the fact that NASCAR isn't just for Southerners anymore

- Give up that subscription to Artforum and start reading Maxim instead

Sunday, October 23, 2005

Editing the Subtitles

In that spirit, here are more appropriate subtitles for two stinkers that I saw today.

- At the Whitney, "Oscar Bluemner: A Passion for Red Buildings"

- At MoMA, "Elizabeth Murray: Prelude to Pixar"

Thursday, October 20, 2005

The Church and Contemporary Art

The church, of course, was the greatest of arts patrons for much of the second millennium. That changed, though, during the nineteenth century. Spence quotes Monsignor Timothy Verdon, director of the Office for Evangelization Through Art in the Florence Archdiocese, on why this is. “The Church found itself patronizing artists who were opposed to the avant-garde,” Verdon says. “The image it projected between the 1830s and 1940s was backward-looking in an age that increasingly felt the past was irrelevant.”

As part of Vatican II, Pope Paul VI attempted to change this situation with an affirmation of contemporary art’s place in the liturgy, but local clergy did not embrace the new. What emerged, according to Verdon, was “a sad parody of contemporaneity in the vestigial echoes of Fra Agelico style.”

The most interesting part of Spence’s piece, though is the discussion of the church’s strong preference for figuration over abstraction. The church’s official position is that artwork must “express the liturgy,” and as a result those charged with commissioning art for church spaces tend to default to figurative work.

Spence quotes a priest from an Italian parish explaining why liturgical art should be figurative. “The Church, in general,” he says, “is for simple people and they must be able to understand.” (This patronizing of parishioners might help explain why regular church attendance across Italy declined from 70% of the population to 40% over the second half of the last century.)

But it’s not only the Italian church that struggles with how to integrate art into the liturgy to create a suitable worship experience. Closer to home, New York artist Gwyneth Leech has received criticism recently over a cycle of figurative paintings representing the stations of the cross. Commissioned by an Episcopal church, Saint Paul’s on the Green, in Norwalk, CT, Leech chose not only to set the paintings in the present day (a tradition that goes back to the middle ages), but also to situate the narrative in the context of war. (Station 1: Jesus is Condemned to Death is at right.)

But it’s not only the Italian church that struggles with how to integrate art into the liturgy to create a suitable worship experience. Closer to home, New York artist Gwyneth Leech has received criticism recently over a cycle of figurative paintings representing the stations of the cross. Commissioned by an Episcopal church, Saint Paul’s on the Green, in Norwalk, CT, Leech chose not only to set the paintings in the present day (a tradition that goes back to the middle ages), but also to situate the narrative in the context of war. (Station 1: Jesus is Condemned to Death is at right.)Of her choices, Leech says, “I was asked to combine the traditional stations iconography with elements of the world we live in. This brief eventually led to my vision of Christ as a prisoner of war, and as a hostage tortured by insurgents. The crowds are refugees. The people weeping at the foot of the cross are grieving Iraqis and Americans who have lost family members to bombs and to violence.”

The question of how well Leech’s contemporary iconography integrates with the historical narrative remains open. There is no question, though, that Leech’s paintings have caused controversy in Norwalk. The reason for this, I believe, is similar to the reason that the Italian priest gave for restricting liturgical art to figuration: certain people are not able to see an object, understand metaphor, and make the leap to the concept that stands behind the object at hand.

Corporate curators made a realization half a century ago. By replacing figuration with abstraction in the art they commissioned for public buildings, they were able to remove the possibility that conflict would arise about the art’s subject matter. It might be time for the church to examine that strategy now—and to rethink whether the liturgy must be supported with representational art.

But there would be a secondary benefit as well. In her FT piece Spence quotes Danilo Eccher, director of Rome’s Museum of Contemporary Art on the applicability of figuration for today’s religious art. “Medieval man needed frescoed churches because at home he had nothing, but we are bombarded daily by images. Contemporary man therefore has need of a space for secret emotion, in silence more than in image.” What better way to create a meditative space suitable for worship than to remove all reference to the stresses of the everyday world?

Tuesday, October 18, 2005

The Forty-Part Motet

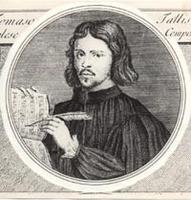

With its recent installation of Janet Cardiff's The Forty-Part Motet MoMA has created what has to be one of the most sublimely beautiful spaces in Midtown Manhattan. (An installation view is at right.) It's not fashionable these days to use words like "sublime" and "beautiful" without scare quotes, but I'm simply at a loss for how to describe the work without them.

With its recent installation of Janet Cardiff's The Forty-Part Motet MoMA has created what has to be one of the most sublimely beautiful spaces in Midtown Manhattan. (An installation view is at right.) It's not fashionable these days to use words like "sublime" and "beautiful" without scare quotes, but I'm simply at a loss for how to describe the work without them.Cardiff's piece, for those not familiar with this well-traveled sound installation, is a recording of Thomas Tallis's polyphonic choral work from 1575, Spem in alium. Tallis's Latin text translates this way:

I have never put my hope in any other but in you God of Israel who will be angry and yet become again gracious and who forgives all the sins of suffering man. Lord God Creator of Heaven and Earth look upon our lowliness.For this piece, Cardiff recorded each of the forty unique vocal parts individually. The installation consists of forty speakers arranged in an oval, each speaker playing back a voice of one member of the Salisbury Cathedral Choir. Cardiff's advanced recording and playback technology creates the experience of a live performance that typical two-channel playback cannot. The elliptical installation gives visitors the ability to move around and through the sound in a way that is not possible when the piece is performed by a live choir.

Simply put, the recording stuns. If, as the choir crescendos, you don't feel a shiver rise somewhere inside you, you have to be emotionally tone deaf. Both times I've visited the piece in the last few weeks, I've fought to hold back an involuntary display of emotion. As I struggled to keep my eyes dry, I looked around the gallery space and saw others furtively wiping their eyes, hoping that no one else was noticing.

I've already decided that while this piece is installed over the next year it will become a regular lunch hour stop when I am working in New York. I'll be curious to see, though, just how my reaction to the piece will change the more that I experience it because in trying to determine what about the piece gives it such emotional power, I've realized that it's not anything in Cardiff's work.

The Forty-Part Motet takes all of its emotional punch from the choir's performance of Tallis's piece. Most serious singers include Spem in alium on the short list of works they want to perform some day because the piece creates a sound environment that is unique and that (prior to Cardiff's work) could not be adequately reproduced using recording technology.

The Forty-Part Motet takes all of its emotional punch from the choir's performance of Tallis's piece. Most serious singers include Spem in alium on the short list of works they want to perform some day because the piece creates a sound environment that is unique and that (prior to Cardiff's work) could not be adequately reproduced using recording technology.In her piece Cardiff has harnessed the power of a live performance by using the skills of a master recording technician. She does not add to the effect of a live performance of Spem in alium; rather, she optimizes the recording of the performance to recreate the effect of a live event better than any recording engineer has been able to do to date. Unlike her other work where she creates original sound environments, here Cardiff has recreated a sound environment originally developed over 400 years ago.

Filtered through Cardiff's technology, the music sounds good enough to make listeners choke up. I can't help but wonder, though, if I will continue to have that experience over repeated visits. I still become emotional every time I hear the final movement of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony performed live. But that only happens for me a couple times a decade. I wonder if listening to Cardiff's recording of Spem in alium once a week over the next year in this walk-in sound chamber will dull my sensibilities to the work. I question whether the technological mediation of my experience of the piece of music will get in the way of my continued appreciation for the performance that has been recorded.

The magic of a live performance (recreated so well here) may be just that--magic created by real people in a passing moment in time. When that performance repeats exactly every fourteen minutes all day every day, the magic may dissipate. Only time will tell if Cardiff's piece has the staying power of the original, unmediated Spem in alium. I hope that it does, but I'm not sure that it will.

Monday, October 17, 2005

Current Chelsea Picks

Adam Cvijanovic’s latest show at Bellwether, Love Poem (10 Minutes After the End of Gravity), has received ample coverage since it opened. There’s good reason for that. His 14 x 75 foot painting on Tyvek (at right) feels like a reimagined, apocalyptic version of an early-1970s realist piece. The staples of suburban America (tract homes, cars, and consumer products ranging from bottles of Diet Coke to Pop Tart boxes to Glad trash bags) become weightless detritus as they float off into space, unmoored after the suspension of the law of gravity. This feels like a painting that would never have been done if it weren’t for the events of September 2001 when we realized that disasters did not have to be solely of the predictable, natural type.

Adam Cvijanovic’s latest show at Bellwether, Love Poem (10 Minutes After the End of Gravity), has received ample coverage since it opened. There’s good reason for that. His 14 x 75 foot painting on Tyvek (at right) feels like a reimagined, apocalyptic version of an early-1970s realist piece. The staples of suburban America (tract homes, cars, and consumer products ranging from bottles of Diet Coke to Pop Tart boxes to Glad trash bags) become weightless detritus as they float off into space, unmoored after the suspension of the law of gravity. This feels like a painting that would never have been done if it weren’t for the events of September 2001 when we realized that disasters did not have to be solely of the predictable, natural type.Jeremy Blake’s newest film, Sodium Fox, is showing at Feigen Contemporary, and it shouldn’t be missed. Don’t bother with the static works in the front gallery, though. Head straight to the rear room where the film is being screened. Blake’s video work is all about mood, atmosphere, and the movement of color over time. The stills for sale out front do not, and cannot, do justice to the mesmerizing experience of watching his contemporary consumeristic landscape emerge and morph.

I also liked several things in the inaugural group exhibition, Set It Off, at the new James Nicholson Gallery. But since I already wrote about half the pieces in the show, I’m not going to plug them again. I’ll just say that it looks like someone took the advice in my final paragraph, cherry-picked the best work from last summer’s Artists In the Marketplace (AIM 25) exhibition, and stuck price tags on the pieces. That’s proof, I guess, that the Bronx Museum program works.

Monday, October 10, 2005

Slow Week

Update: No sooner do I post the above than MAN goes ahead and runs my piece. Well, it's not exactly my piece because I hadn't actually written it yet. But Tyler says almost exactly what I had intended to say about MoMA's new installation in this post from this morning. So follow the link and read him. I do, though, have more in-depth thoughts on Janet Cardiff's The Forty-Part Motet that I will run later this week.

Friday, October 07, 2005

Two Worth Reading

Greg gets all righteously indignant (and justifiably so) over the destruction of a landmark piece of modernist residential architecture--Gordon Bunshaft's Travertine House. Martha deserves another trip to the pokey for her role in this one.

Thursday, October 06, 2005

BCN Notes

Parc Güell: Antonio Gaudí's work fascinates me because of its utter originality. His slightly warped melding of natural and man-made forms into built spaces (the park's gatehouse is at right) is unlike anything anyone had done before or since. His work on this park opens a dialogue between landscape and structural architecture that is conducted in Gaudí's own private language. I'm not sure I understand everything he says, but it sure is fun to listen.

Parc Güell: Antonio Gaudí's work fascinates me because of its utter originality. His slightly warped melding of natural and man-made forms into built spaces (the park's gatehouse is at right) is unlike anything anyone had done before or since. His work on this park opens a dialogue between landscape and structural architecture that is conducted in Gaudí's own private language. I'm not sure I understand everything he says, but it sure is fun to listen.The Picasso Museum: If you want to see Picasso qua Picasso, you're better off going to MoMA. But walking through the extensive collection of pre-Blue Period work here (donated by Picasso himself in 1970) allows you to see Picasso becoming Picasso in a way that you can't anywhere else.

National Museum of Catalunian Art: I'm prone to be suspect of collections that are assembled and curated for nationalistic purposes. So I was pleasantly surprised by the incredible quality, richness, and depth of work at MNAC. With pieces spanning the 12th to the mid-20th century, the museum's collection can really stand on its own against any historical collection worldwide--which is probably just what the Catalunian government wants me to say about it.

Wednesday, October 05, 2005

Gettygate

As the revelations keep coming, though, I can't help but think that we've heard this whole story before. A low-level operative gets busted for committing a crime. Some diligent, sleuthing local reporters continue to chase the story, following it all the way to the top. Eventually the leader steps aside as criminal prosecution appears imminent.

As the revelations keep coming, though, I can't help but think that we've heard this whole story before. A low-level operative gets busted for committing a crime. Some diligent, sleuthing local reporters continue to chase the story, following it all the way to the top. Eventually the leader steps aside as criminal prosecution appears imminent.If you're interested in drama and suspense here, you might as well change the channel. We all know how this one is going to end, thanks to Woodward and Bernstein's playbook. Let's just hope the journalists at the LA Times stick to the game plan: 1) follow the money and 2) keep asking, "What did the president know and when did he know it?" The sooner they can press Nixon to step onto Marine One to fly off into the sunset, the better. And this time there's not going to be a crony waiting at the ready with a Get out of Jail Free card.

Tuesday, October 04, 2005

A Lesson to Learn from Boston's Mistake

Don't miss the review that has been posted there. The author raises several interesting and valid points that those of us who haven't seen the show wouldn't have been able to make. He weighs in with this final comment, "But the problem isn't one of ethics, as it sometimes is portrayed, at least not at the root: rather, it's a one of judgment and taste."

Museums can take away an important lesson from JL's commentary: pick your potential donors carefully. It sounds like the MFA hasn't done an especially good job of that in this case.

Monday, October 03, 2005

World Weary and Wondering

Three weeks isn't really a long time, but during that period I came to feel horribly out of the art world loop: no Artnet or ArtInfo, only the briefest of moments to skim the Arts section of The New York Times on-line, and (aside from one or two of my favorites) no blogs. I missed the whole fall opening season in Chelsea, and I'm still grumbling about not being able to see Floating Island.

I had wanted to get out to see a few shows last Saturday in Williamsburg and Chelsea, but I wasn't able to make that happen. I did, though, have a chance to open my blog aggregator for the first time in weeks and spent some time trolling through the hundreds of posts I didn't see as they were published last month. I don't yet feel caught up with all that I missed last month, and I don't quite feel like I will be able to catch up fully.

It didn't used to be that way. I'm not thinking about the situation at some point in the distant past here. I'm remembering only as far back as the spring and summer of 2004.

Just a little more than a year ago, when I started this blog, there were probably less than 20 art blogs being published. Using an aggregator it was possible to read through the universe of art blogs once a week in a 30 minute sitting. Now, I hear, there are over 400 art-related blogs being published. I have a hard time keeping up with the good ones every week--let alone with the other 380 out there. Artnet is publishing must-read content just as frequently as ever--if not more so. ArtInfo now provides pointers to many additional items every day, doubling or tripling the number that ArtsJournal already highlights. And then there are the monthly glossies to skim through. It feels like there is an order of magnitude more information that needs to be managed on a daily basis today to remain an insider than there was only a year ago.

A similar explosion has happened on the gallery scene in Chelsea. Before I started the blog, I could pretty much cover Chelsea in a part of a day. (Granted, when I do a comprehensive gallery run through it really is that. I'm in and out of a gallery in less than a minute if I don't see something that interests me.) I can't do that any more. With new spaces and new buildings on whole new streets, I can't cover the neighborhood thoroughly in a day anymore.

All this makes me wonder two things. First, if I will ever get back ahead of the curve--especially with more overseas travel on the calendar. And, second, if there is really enough interest in contemporary art today to support all the galleries and sources of commentary that have emerged in just the last year.

I think the answer to the first is "yes," with time. I'm not so sure that the answer to the second is the same.

Wednesday, September 28, 2005

Checking in, Checking out

It's not that I don't have much to say. I have some thoughts sketched out on several Barcelona art spots I've managed to see--the Picasso Museum, the National Museum of Catalunyan Art, and Antoni Gaudi's Parc Güell--but I haven't had the time to do any writing. And I won't for the near future.

Until I'm back in blogging action, check out some of the other art blogs listed in the right hand navigation bar.

Friday, September 23, 2005

It Doesn't Exist if It's not Free

This example perfectly illustrates the limitations of the paid-content business model and shows why media organizations that charge for their content are ceding their relevance to other providers.

In order for content to become part of the broad cultural discussion, it needs to be made available for free, and it needs to remain free over time. Publications like The Wall Street Journal that charge for new content and like The New York Times that charge for access to archived content are sacrificing their long-term cultural relevance for short-term profitability.

Before the age of the Internet, the ability to distribute content gave power. The words of a journalist or critic that were backed by the power of an editorial function, a printing press, a fleet of delivery trucks, and a network of distribution outlets dripped with an authority that was conferred by this complex enterprise.

With the advent of the Internet, these distribution barriers broke down. Anyone with technical know-how could develop a website and make his thoughts available to the world. With the subsequent development of blogging software, the remaining barriers disappeared. Today, one doesn’t even need to have basic technical skills to publish a website.

There is only one barrier to entry remaining for someone who wants to become a voice in the culture at large: the ability to think and write clearly. Granted, that’s still a large barrier, but there have always been more people interested in being journalists and critics than there have been publications to support them. Today one doesn’t need the backing of a major publication to develop a voice and establish a dedicated readership.

Today the editorial, printing, and distribution functions have almost no impact on how a writer develops credibility and reaches an audience of readers. Readers are rapidly migrating away from pay-for-use information services (in print or on the web) and turning to free sites hosted by print publications and to other information providers (like bloggers) for current cultural content. Researchers are becoming more reliant on search engine results for information and less reliant on proprietary systems and pay-for-use archives. By hiding their writers behind a curtain that readers must pay to open, mainstream publications are diluting their historical roles in the culture as conveyors of information and tastemakers.

Content wants to be free. It’s never truly free to distribute content, although with the Internet the costs have decreased significantly. But as long as mainstream publications continue to charge for their content, their cultural influence and relevance will continue to decline. And their writers will continue to whine that nobody reads them or gives them credit for their work.

Wednesday, September 21, 2005

And That's Different How?

The account in the paper of record leaves me with a couple key questions that I wish Vogel would have addressed:

- What's really different now that these two have new titles? With his expansion lust, I doubt that Krens was really involved in the day-to-day management of the New York museum. Does Dennison actually take on more responsibility and authority with her promotion from deputy director, or is this just an acknowledgement of work she has been doing and an attempt to keep her from jumping to another museum to get a new title?

- Does this move indicate that the board is trying to exercise power to reign in Krens, or is it actually freeing him from management responsibilities in New York so that he can turn up the gas on his plans for buidling a global footprint for the Guggenheim?

Tuesday, September 20, 2005

My Latest Acquisition

I made the decision some time ago not to write about anything in the collection. As readership of the site has grown, I have wanted to avoid the appearance that I’m using it to enhance the value of works I own.

But I’m going to make an exception today for three reasons. We recently came to own a piece of art that has no commercial value. My writing about it here can have no impact on the market value of the artist’s work. And the story of how it came into our hands is interesting enough to share.

Because I’m on this extended assignment in Europe and won’t have the chance to return home for several weeks, I decided to take Mrs. FtF and the kid with me to Barcelona.

Last Wednesday when I returned from the office I noticed a black and white Polaroid on the coffee table in the living room of the apartment we’re renting. It was a portrait of the two of them sitting on the grass in the Parc de la Ciutadella which is a few blocks from where we are staying.

Last Wednesday when I returned from the office I noticed a black and white Polaroid on the coffee table in the living room of the apartment we’re renting. It was a portrait of the two of them sitting on the grass in the Parc de la Ciutadella which is a few blocks from where we are staying.I asked Mrs. FtF where she got it. She was walking the baby through the park, she told me, when a woman who had been following them approached and asked if she could take their picture. Thinking that the photographer was someone accosting tourists to make a few Euro, I asked what she paid for it. Nothing, she told me. The photographer gave it to her.

I looked at the print more closely and realized that it wasn’t just a snapshot. It’s a nicely composed photograph. The two of them had been thoughtfully posed and framed.

Mrs. FtF and the photographer talked before and during the shoot, and the photographer told her that she was traveling to different cities, photographing people who use parks. She had been in New York the week before.

She took two test Polaroids of Mrs. FtF and the kid. Then it started to rain, and she decided not to finish the shoot. Her assistant gave Mrs. FtF one of the Polaroids, and they packed up their gear. End of story.

Well, almost.

Over the weekend, I picked up the map Mrs. FtF has been using to navigate around the city and noticed something written on the back page in a handwriting that I didn’t recognize. When I read the text I did a double take. It was an email address, and there was no mistaking whose it was.

I asked Mrs. FtF if the email address belonged to the person who had photographed her earlier in the week. It did. The photographer wrote it there so that Mrs. FtF could stay in touch to find out how the project was progressing.

And that’s how I came to realize that we now own an unsigned, 4x6 inch Rineke Dijkstra portrait of the wife and kid.

Sunday, September 18, 2005

What I Missed; What I’ll Be Missing

This weekend I also (almost) missed Carol Vogel’s Friday exclusive: the announcement of a date for the Pierre Huyghe extravaganza on the ice rink in Central Park that I mentioned last year. October 20, Vogel reports, is when the fun will occur. I’m afraid I’m going to have to miss that too—much as I had been looking forward to seeing the madness in person.

Next weekend I’m going to have to miss a public project in my own neighborhood that looks like it will be interesting. Elaine Gan, a participant in this year’s Bronx Museum AIM 25 program, will be controlling crowd movement through the public space of Sara D. Roosevelt park. There is a simulation of what the piece will look like available here. Browse to the top level of the site to see documentation of several other similar projects.

Finally, according to The Art Newspaper, it looks like I missed the chance to invest in ABN-AMRO’s fund of art funds which has been unceremoniously closed down due to lack of market interest. As much as I love the private equity and hedge fund guys, I have to say that I’m glad that the financial markets aren’t quite ready to treat art as just another type of commodity to trade. Hopelessly romantic of me, I know.

Thursday, September 15, 2005

Animal Sounds

I'm currently 3800 miles away from the east coast of the United States, and I can clearly hear two common calls of the species homo artus: a critic's wail of frustration at being unable to find a mating partner and an alpha-male collector's chest-thumping display of dominance.

Monday, September 12, 2005

An Imaginary Conversation

Stanley Brouwn: What am I doing here?

SP: Well, you were so busy counting how many steps it took you to walk across the city that you didn’t notice that bus speeding down the street.

SB: I was afraid that would happen one day.

SP: I suppose you know the drill, but let me review the process for you anyway. You’re here at the Pearly Gates. You get one chance to show me what you did with your life, and then I make the decision about whether to open them for you or to send you to that other place.

SB: OK.

SP: So, I notice that you have a career retrospective on view now at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Barcelona. Are you happy with the show?

SB: Yeah, I mean, it pretty much covers what I’ve spent the last 45 years of my life doing—the index cards, the measuring of distances, the stainless steel measuring sticks, the counting of steps. I’m really happy with the show. The curators did a fabulous job installing it, and I think it looks great in the galleries. The show pretty much gives you a complete picture of my life's work. My reputation can rest on it. So you’ve seen the show?

SP: I see everything.

SB: I suppose so. OK, then. Go ahead and make your judgment based on that.

SP: Are you sure you want me to do that? I mean, a life spent making index cards and measuring distances? That's not much to show, really, for your final accounting.

SB: You think?

SP: I do. But my records indicate that otherwise you’ve been a pretty good guy. If you ask nicely, I might be willing to give you a mulligan.

stanley brouwn is on view through September 25 at the Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona.

Wednesday, September 07, 2005

Own Your Own Flavin

Dan Flavin must have known that he had made his breakthrough with the diagonal of May 25, 1963 (to Constantin Brancusi) (at left) because he decided that one copy wasn’t enough. He specified that the piece be executed with nine different fluorescent tubes (yellow, daylight, cool white, warm white, soft white, blue, green, pink, and red), each one in an edition of three.

Dan Flavin must have known that he had made his breakthrough with the diagonal of May 25, 1963 (to Constantin Brancusi) (at left) because he decided that one copy wasn’t enough. He specified that the piece be executed with nine different fluorescent tubes (yellow, daylight, cool white, warm white, soft white, blue, green, pink, and red), each one in an edition of three. In this way, Flavin starting playing in the emerging minimalist/conceptualist space. Variability of a single attribute—the color of the light—became for him a consideration worthy of exploring. Flavin had originally intended to vary the positioning of the fixture on the wall as well, but he eventually decided to limit that variable to the 45 degree angle of the initial piece.

In this way, Flavin starting playing in the emerging minimalist/conceptualist space. Variability of a single attribute—the color of the light—became for him a consideration worthy of exploring. Flavin had originally intended to vary the positioning of the fixture on the wall as well, but he eventually decided to limit that variable to the 45 degree angle of the initial piece.The catalogue says that two pieces from this series of 27 have never been executed and are (theoretically) still available for purchase from the estate. Interested in buying one of these historically important Flavin works? There is one available in warm white and another in soft white.

Of course you could always just buy an eight-foot fixture and the correct bulb from The Home Depot and install it yourself at a 45 degree angle from the floor. But that would be a bootleg, and we could never condone bootlegging art here, could we?

Tuesday, September 06, 2005

Ten Things I Think Today

- The Met has closed the whole wing housing the Robert Lehman collection. I think the closure is due to this post.

- OK, I think not. I think it has to do with this fall's Fra Angelico exhibition planned for the space. I think it will be a great show. (Update: Someone emailed me this morning saying that there has been water damage in the wing and that's why it's closed right now. I think that would explain the scaffolding and plastic sheeting I saw. I also think that if this is true the Met is being disingenuous with that little sign blaming the closure on preparations for the new installation.)

- I think MoMA has finally gotten an atrium installation right. Cy Twombly's The Four Seasons is scaled perfectly for the wall where it has been hung. I think it's going to be difficult (if not impossible) for MoMA to continue to come up with works that harmonize so well with this difficult space.

- I think the current Matisse show at the Met has been the surprise hit of the summer. Who would have thought that a show about a painter and fabric could be so interesting? I sure didn't.

- I think somebody totally overpaid when he bought Robert Rauschenberg's Rebus (at right) for MoMA. Sure, it's a great example of Rauschenberg's work from the mid-1950s, but don't you think that for $30M MoMA should gotten a taxidermied animal or two? Too bad it's not kosher to add one at this late date. I think several of the specimens on this site could really complete the piece.

- I had been thinking that the kid was a budding art critic because I can throw her into the Baby Bjorn and she'll be content to spend an afternoon looking at art. But she was just as happy recently when we spent an hour wandering the aisles of a farm supply store in the Midwest. I'm not sure what to think of her fascination with cowboy hats, DIY veterinary tools, Wrangler jeans, electric fencing, and plumbing fixtures.

- I think I'm much more happy with MoMA's new fourth floor installation of the Monet painting formerly known as Water Lilies. It's still not shown as well as it was in its old home, but it looks much better in this gallery than it did in the atrium.

- I think (while I'm on the topic) that nostalgia for the old MoMA isn't necessarily a bad thing. Visiting MoMA now is a much different experience than it used to be, and I think it's healthy that people remember that. Something was lost when MoMA bulked up with its Taniguchi addition and started drawing such monstrous crowds. When I was there last Sunday afternoon I couldn't enjoy anything in the permanent collection because the galleries were simply too crowded. Greg can whine all he wants about people whining about the new MoMA, but here's the fact: it's almost impossible to have a fulfilling art-viewing experience there anymore.

- I think I have one more Dan Flavin post left in me after my recent visit to the exhibition in Chicago. I think I'll save it for tomorrow.

- I think the next few weeks will be somewhat quiet around here. I'm heading overseas for an extended stay. When I'm not working, I'm going to do a little more enjoying of the good life on the Mediterranean coast and a little less blogging. But, then again, I said I was going to take last week off, and the site (for some strange reason) seems to have a post made almost every day.

Saturday, September 03, 2005

Graphic Design/Evangelism Consultant Needed

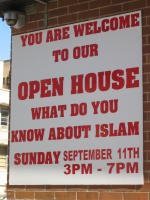

In his May 2005 Artforum Top Ten, Tim Davis included the signage outside the mosque in his neighborhood:

In his May 2005 Artforum Top Ten, Tim Davis included the signage outside the mosque in his neighborhood:I arrived back home in New York yesterday and passed the mosque while running an errand. Here's a snapshot of a new sign that has gone up there sometime over the last couple weeks while I've been away.GOD AND GRAPHIC DESIGN My neighborhood mosque, Madina Masjid at Eleventh and First, recently solved one of the great graphic design-based theology problems since the Jews figured out how to spell YHWH. "THERE IS NO GOD" their sign used to read, in foot-high green sans serif type. The second line, much smaller, magenta, and punctuationless, went on, "but allah mohammed is the messenger of allah." The sign's been changed now, but if only more houses of worship would advertise that there is no God, perhaps the world would emerge from its latest dark age.

If mosque members would have asked any of their East Village neighbors what the worst possible day of the year would be to hold this event, four out of five respondents would have given this date as their answer. Attendance, I predict, is going to be more spotty than a Damien Hirst dot painting.

Thursday, September 01, 2005

The Long Road to Simplicity

Included in the Flavin show is a very telling, small work on paper—a poem, actually. When he completed the piece, Flavin dated it at the bottom on the sheet: 10/2/61.

The poem has been used on an exhibition website and in gallery brochures, but one fact about it has been overlooked: Flavin wrote this a full year and a half before allowing himself to create a piece that was nothing more than a shimmering fluorescent pole.

Somehow, he knew what he wanted to do as early as 1961, but he didn’t allow himself to get there while working in his studio until May of 1963.

Wednesday, August 31, 2005

Simplify, Simplify

As I walked through the Dan Flavin retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago last weekend, I couldn’t help but think of what Henry David Thoreau wrote in Walden more than 150 years ago, “Simplicity, simplicity, simplicity! I say, let your affairs be as two or three, and not a hundred or a thousand.... Simplify, simplify.”

As I walked through the Dan Flavin retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago last weekend, I couldn’t help but think of what Henry David Thoreau wrote in Walden more than 150 years ago, “Simplicity, simplicity, simplicity! I say, let your affairs be as two or three, and not a hundred or a thousand.... Simplify, simplify.”The first gallery of the installation dramatically shows what happened when Flavin simplified his approach to art making. As Thoreau suggested, Flavin’s work became a completely different thing, a much better thing, as the complexity was boiled away.

In 1963, Flavin distilled his work down to a single element—light. With the diagonal of May 25, 1963 (to Constantin Brancusi) (at left), Flavin moved from using lit bulbs to enhance monochromatic Masonite panels to presenting the effect made by the bulb as the art object.

Flavin’s move toward radically simplifying a style he had worked to develop reminded me of a similar path Mark Rothko took in 1949—a path that was wonderfully illustrated in the Pace Wildenstein exhibition, Mark Rothko: A Painter’s Progress, The Year 1949. Over 1949 Rothko simplified the compositional field in his work until he finally ended up with what came to be seen as his signature style—two or three simple rectangular bands of color floating on a background.

These two paths toward simplicity should serve as case studies for young artists today. Often it’s finding the essential kernel of the work and paring back everything but that—painfully difficult as it is to do—that leads to the development of a clear, unique, mature style.

Tuesday, August 30, 2005

Embarrassment by Riches

Today, though, The Boston Globe has changed my opinion of Rogers's aggressive fundraising tactics with a piece on the MFA's newest exhibition--a vanity show (including yachts!) of money-man William Koch's unfocused collection.

By currying favor with a prominent collector in this way, Rogers has seriously damaged the institution's credibility--essentially turning it into a gallery space for rent. (Ralph Lauren last month. Koch this month. Who's next?) Rogers must know he's on shaky ground here. In the piece he defends the show by comparing it to what the Guggenheim has done lately. Trying to pass off the Guggenheim as the paradigm of integrity? Please.

Neither Rogers nor Koch seems to realize how transparent the driver is behind Rogers's decision to mount the exhibition. Can't either of them see that the courtesan position the MFA has assumed by hosting this show creates a situation that is an embarrassment to both of them personally and to the MFA as an institution?

I wonder if anyone on the MFA's board can see it. I sure hope so. And I hope board members decide to take action. Things have gone too far off course in Boston. It's time for a correction burn. I wasn't convinced of that earlier, but I am now.

Related: Modern Art Notes on this "giant slurp job."

Monday, August 29, 2005

Word of the Day

Cézannepicassosurrealismabexminimalismpop

Tuesday, August 23, 2005

On the Lam

Monday, August 22, 2005

Bottling Street Art’s Juice

There’s always a tension that arises when the art establishment embraces a form of popular expression. Street art (when did it stop being “graffiti”?) serves as an interesting example.

There’s always a tension that arises when the art establishment embraces a form of popular expression. Street art (when did it stop being “graffiti”?) serves as an interesting example.The genre has its roots in non-commercial, rebellious expression. The interesting question here is how the gallery system can create value around an object that is typically given away, around a practice that is anarchic, and around an experience with the object that is by its nature transitory.