Tuesday, December 27, 2005

Spectacle, But Not Much Else, in the Turbine Hall

For many artists, the chance to do a work for the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall must be the commission of a lifetime. It also has to be a challenge unlike any they have ever faced. That’s what makes it so interesting to see the resulting works.

The scale of the space almost ensures that anything commissioned for it will partake of spectacle. Anish Kapoor’s 2002 installation Marsyas and Olafur Eliasson’s The Weather Project from 2003 certainly did. Bruce Nauman’s soundscape Raw Materials from last year, on the other hand, did what Nauman does so well by taking a contradictory stance—negating the assumption of visual spectacle to leave viewers with a pure audio experience.

Rachel Whiteread’s current installation in the space, Embankment (at right), achieves a moderate level of success. The element of spectacle is at play in the work to a degree sufficient to make the installation interesting. But Whiteread’s concept and use of materials do not rise to a level that would make the work truly memorable.

Rachel Whiteread’s current installation in the space, Embankment (at right), achieves a moderate level of success. The element of spectacle is at play in the work to a degree sufficient to make the installation interesting. But Whiteread’s concept and use of materials do not rise to a level that would make the work truly memorable.

Whiteread has filled the Hall with casts of boxes—thousands of them. The installation has the requisite conceptual framework for a major piece of contemporary art. Whiteread has spoken about finding inspiration for the installation in an old box that once belonged to her mother. She layers on top of this personal memory a pop cultural reference by talking about the impression made on her by the final scene in Raiders of the Lost Ark where the Ark of the Covenant is boxed up and placed in a generic warehouse somewhere. She also talks about the process of casting and making a negative and then a positive image of her mother’s old box and the philosophical implications thereof.

It’s all the right talk for a major commission like this, but none of it really matters. The power of the piece comes from the massive assemblage of items Whiteread has created. It doesn’t matter that the stacks she has created are made of casts of casts of objects. It doesn’t matter that the items cast were boxes. The work is all about the stacking—the massing of objects—and the viewer’s experience of walking through them.

If you enter the building from the Thames side, you come in one level above the installation and have the opportunity to view it from a balcony. Seeing it from this vantage point provides a completely different experience than going down to the ground floor and walking through the labyrinth that the Whiteread has made.

When you walk among the piles (at right), you begin to feel vulnerable. Your body, in comparison to these massive towering piles, feels small. You feel a sense of endangerment as you pass between the stacks.

When you walk among the piles (at right), you begin to feel vulnerable. Your body, in comparison to these massive towering piles, feels small. You feel a sense of endangerment as you pass between the stacks.

The piece, in this way, partakes of the what Michael Fried called the theatrical nature of minimalism. It does so, though, to a much greater degree than any piece of minimalist work I know. In a way, walking through this installation feels like walking through one of Richard Serra’s torqued ellipse. You feel like your life could be threatened at any moment by a strong gust of wind or a small tremor of the ground.

Whiteread’s installations takes a shortcut this way. The piece is all show (a great experience) but no tell as it lacks an instigating concept as interesting as the “wow!” experience of walking through the piece. She has tried to provide one, but the concept is weak. It can’t stand up to the impression made by the objects.

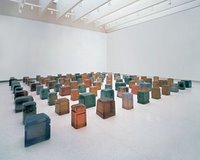

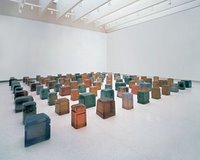

Seeing Whiteread’s installation in the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall brought back to mind her piece that was installed in the Guggenheim’s rotunda as part of the Singular Forms (Sometimes Repeated) show in 2004. This untitled piece (at left), 100 colored resin casts of the space beneath chairs, is much more subtle and meditative than the Turbine Hall installation. It doesn’t create spectacle in any manner. But to me it it’s the more interesting of the two works.

Seeing Whiteread’s installation in the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall brought back to mind her piece that was installed in the Guggenheim’s rotunda as part of the Singular Forms (Sometimes Repeated) show in 2004. This untitled piece (at left), 100 colored resin casts of the space beneath chairs, is much more subtle and meditative than the Turbine Hall installation. It doesn’t create spectacle in any manner. But to me it it’s the more interesting of the two works.

The meditative feel of the untitled work forces contemplation of the concept in a way that the Turbine Hall installation doesn’t, and the colored resin used for the casts provides more visual interest. The work stands on its own—it speaks for itself—in a way that the Turbine Hall installation doesn’t. The piece doesn’t rely on the shock of spectacle to make its impression.

For this more recent commission, Whiteread has taken the easy way out by falling back on the crutch of spectacle that the massive space provides to her, and she allows spectacle to carry the work rather than creating a piece that uses the space in an interesting way that integrates with and supports the concept and materials she has chosen for the installation.

That said, I would still jump at the chance to spend a half hour walking among Whiteread's boxes if the opportunity presented itself again.

Rachel Whiteread’s Embankment is on display in the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall through April 2, 2006.

The scale of the space almost ensures that anything commissioned for it will partake of spectacle. Anish Kapoor’s 2002 installation Marsyas and Olafur Eliasson’s The Weather Project from 2003 certainly did. Bruce Nauman’s soundscape Raw Materials from last year, on the other hand, did what Nauman does so well by taking a contradictory stance—negating the assumption of visual spectacle to leave viewers with a pure audio experience.

Rachel Whiteread’s current installation in the space, Embankment (at right), achieves a moderate level of success. The element of spectacle is at play in the work to a degree sufficient to make the installation interesting. But Whiteread’s concept and use of materials do not rise to a level that would make the work truly memorable.

Rachel Whiteread’s current installation in the space, Embankment (at right), achieves a moderate level of success. The element of spectacle is at play in the work to a degree sufficient to make the installation interesting. But Whiteread’s concept and use of materials do not rise to a level that would make the work truly memorable.Whiteread has filled the Hall with casts of boxes—thousands of them. The installation has the requisite conceptual framework for a major piece of contemporary art. Whiteread has spoken about finding inspiration for the installation in an old box that once belonged to her mother. She layers on top of this personal memory a pop cultural reference by talking about the impression made on her by the final scene in Raiders of the Lost Ark where the Ark of the Covenant is boxed up and placed in a generic warehouse somewhere. She also talks about the process of casting and making a negative and then a positive image of her mother’s old box and the philosophical implications thereof.

It’s all the right talk for a major commission like this, but none of it really matters. The power of the piece comes from the massive assemblage of items Whiteread has created. It doesn’t matter that the stacks she has created are made of casts of casts of objects. It doesn’t matter that the items cast were boxes. The work is all about the stacking—the massing of objects—and the viewer’s experience of walking through them.

If you enter the building from the Thames side, you come in one level above the installation and have the opportunity to view it from a balcony. Seeing it from this vantage point provides a completely different experience than going down to the ground floor and walking through the labyrinth that the Whiteread has made.

When you walk among the piles (at right), you begin to feel vulnerable. Your body, in comparison to these massive towering piles, feels small. You feel a sense of endangerment as you pass between the stacks.

When you walk among the piles (at right), you begin to feel vulnerable. Your body, in comparison to these massive towering piles, feels small. You feel a sense of endangerment as you pass between the stacks.The piece, in this way, partakes of the what Michael Fried called the theatrical nature of minimalism. It does so, though, to a much greater degree than any piece of minimalist work I know. In a way, walking through this installation feels like walking through one of Richard Serra’s torqued ellipse. You feel like your life could be threatened at any moment by a strong gust of wind or a small tremor of the ground.

Whiteread’s installations takes a shortcut this way. The piece is all show (a great experience) but no tell as it lacks an instigating concept as interesting as the “wow!” experience of walking through the piece. She has tried to provide one, but the concept is weak. It can’t stand up to the impression made by the objects.

Seeing Whiteread’s installation in the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall brought back to mind her piece that was installed in the Guggenheim’s rotunda as part of the Singular Forms (Sometimes Repeated) show in 2004. This untitled piece (at left), 100 colored resin casts of the space beneath chairs, is much more subtle and meditative than the Turbine Hall installation. It doesn’t create spectacle in any manner. But to me it it’s the more interesting of the two works.

Seeing Whiteread’s installation in the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall brought back to mind her piece that was installed in the Guggenheim’s rotunda as part of the Singular Forms (Sometimes Repeated) show in 2004. This untitled piece (at left), 100 colored resin casts of the space beneath chairs, is much more subtle and meditative than the Turbine Hall installation. It doesn’t create spectacle in any manner. But to me it it’s the more interesting of the two works.The meditative feel of the untitled work forces contemplation of the concept in a way that the Turbine Hall installation doesn’t, and the colored resin used for the casts provides more visual interest. The work stands on its own—it speaks for itself—in a way that the Turbine Hall installation doesn’t. The piece doesn’t rely on the shock of spectacle to make its impression.

For this more recent commission, Whiteread has taken the easy way out by falling back on the crutch of spectacle that the massive space provides to her, and she allows spectacle to carry the work rather than creating a piece that uses the space in an interesting way that integrates with and supports the concept and materials she has chosen for the installation.

That said, I would still jump at the chance to spend a half hour walking among Whiteread's boxes if the opportunity presented itself again.

Rachel Whiteread’s Embankment is on display in the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall through April 2, 2006.