Tuesday, March 28, 2006

When the Boundaries Collapse

The typical division of responsibilities in the art world is fairly clear.

The typical division of responsibilities in the art world is fairly clear.Artists create. Dealers make the market. Collectors acquire. Curators contextualize work and present it for public display. Publications staff create printed and web material to extend the reach and impact of the show.

What happens, though, when the boundaries between these functions become elided? When an individual plays more than one role along this spectrum of responsibilities, conflicts of interest emerge. Think of the heat that Charles Saatchi takes regularly for displaying, promoting, and then trading the work that he collects.

But what if one person were to exercise control over every link in the chain from creating to dealing to curating to publishing and educating? How rife for abuse would that situation be?

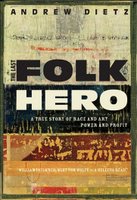

In his new book The Last Folk Hero: A True Story of Race and Art, Power and Profit, Atlanta based writer Andrew Dietz tells just such a story. But rather than flattening and simplifying his characters’ motivations into a easy good vs. bad dichotomy, Dietz provides a neutral presentation that allows the complexity and ambiguity of this unique situation to emerge.

Dietz tells the tale of Bill Arnett—patron, collector, dealer, curator, publisher, and primary promoter of Southern, African-American folk art. Arnett is the genius behind the critically successful and wildly popular Quilts of Gee’s Bend exhibition that has made stops at the MFA Houston, the Whitney, the Milwaukee Art Museum, and eight other venues to date. (The exhibition opened last week at the High Museum in Atlanta.)

While Arnett has assembled work for the exhibition, he isn’t the typical freelance curator. Arnett owns many of the quilts in the show. He could well be making a market in Gee’s Bend quilts in his role as one of the most prolific dealers of Southern vernacular art. Through his company Tinwood Media, he has also published the critically acclaimed catalogue that accompanies the exhibition.

If Larry Gagosian was operating in a similar manner, the art world would cry “foul.” But in Arnett’s case, the situation is different because Arnett, for all his idiosyncrasies (the high strung personality, the constantly updated enemies list, the practice of storing his inventory of art in a leaky warehouse that lacks climate control), is bringing much deserved recognition to artists who have been neglected and/or taken advantage of by other collectors and dealers in the past.

Arnett (a white man) has made a name for himself and has built his business on the work of poor African-Americans, but in Dietz’s presentation Arnett’s activities are undertaken with the best interest of his artists in mind. Without Arnett, it’s probable that Gee’s Bend would still be a town so small and remote that even Google Maps could not locate it. But because of Arnett’s work, the town, the quilters, and their work is now known and appreciated across the country and around the world. And, yes, it’s probably safe to assume that Arnett has made (or will make) a profit on his investment in the quilts, the quilters, and the community as a result.

Dietz doesn’t shy away from the ethical ambiguities that exist in the intersection of roles that Arnett has played in promoting, dealing, and publicizing his artists’ work. And that ambiguity makes for an interesting read. While the book lacks the clear dramatic arc and the easily identifiable heroes and villains of the best non-fiction narratives, the more complex picture he give of his main characters’ intentions is a credit to Dietz’s fairness and balance as a writer.