Thursday, June 30, 2005

A Monument to Disappointment

If you do project-based work in a corporate environment for long enough, you're certain to run across a project that turns out to be impossible to complete to anyone's satisfaction.

If you do project-based work in a corporate environment for long enough, you're certain to run across a project that turns out to be impossible to complete to anyone's satisfaction.Too many people have a political stake of some sort in the outcome. None of them want to be involved or helpful, and no one really cares about the project's ultimate success. But they all need to make sure that what's eventually delivered has some aspect to it that they can use to cover their ass someday in the event of failure.

The team running the project on a day-to-day basis gets fed up with the work. There's no way they can win because the project hasn't been set up to succeed. Every creative, novel, or unique idea they have tried to implement has been killed off by the whim of one stakeholder or another. Team morale plummets. Instead of wanting to deliver a winning solution, they begin wanting the project to be over, no matter how mediocre the final product. So everyone holds his or her nose and puts in long hours to finish off something that no one is proud of.

The individual who holds ultimate responsibility for the work eventually stands up in a big meeting somewhere and presents the results. Everyone involved in the effort knows that the works is mediocre, but no one admits it. (Maybe it's not a total disaster, but it's nowhere near what everyone thought they would be able to deliver in the early, heady days of the effort when anything seemed possible.) Instead, the team leader claims victory, and everyone moves on--hoping that no one asks them if they worked on this project when they interview for their next job. And people on the team will be interviewing for that next job shortly because working on this project has caused them to hate their company, their bosses, their client, and perhaps even their choice of a profession.

This scenario occurs all the time in corporate America. It's just that this week the results of one such project have played out in a very public way on a very large scale--a 1,776 foot scale to be exact.

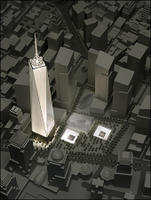

This scenario occurs all the time in corporate America. It's just that this week the results of one such project have played out in a very public way on a very large scale--a 1,776 foot scale to be exact.Behold, Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill's revised plans for the Freedom Tower--disappointment made tangible, on a monumental scale. Or, rather, disappointment that will be made tangible by 2010.

A 200-foot high wall of concrete at ground level--right next to the planned World Trade Center Memorial? Every innovative feature of the somewhat lackluster original design stripped away in this version? Damn it. What a wasted opportunity.

The situation is almost enough to make me nostalgic for the days of Robert Moses, when a single individual with a strong vision had enough political power to realize revolutionary public works. In the absence of that power, we get buildings like this--an embodiment of the lowest common denominator result that occurs when politicians and bureaucrats design by committee and architects agree to do their bidding.

Related: New York Times slideshow of the new design. NY Times architecture critic Nicolai Ouroussoff doesn't attempt to hide his disappointment with the new design.