Monday, April 11, 2005

Arbus Out Loud, Way Loud

One of the pleasures of a single-artist retrospectives comes in the ability to view familiar pieces in the context of the artist’s larger body of works. Occasionally surprises emerge, causing changes of opinion. The Diane Arbus retrospective provides just that experience.

Arbus is best known for her sympathetic photographic portraits of those living on the edges of 1960s American society—from debutante princesses at one end to burlesque performers at the other. Arbus throws in a delightful gaggle of transvestites, ladies who lunch, and nudists for good measure.

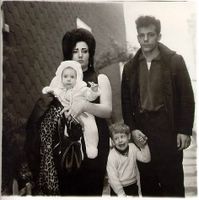

The traveling exhibition now at the Met rolls out all of Arbus’s greatest hits: the identical twin girls, the boy with the hand grenade, the Jewish giant, and the young Brooklyn family with the troubled son.

The traveling exhibition now at the Met rolls out all of Arbus’s greatest hits: the identical twin girls, the boy with the hand grenade, the Jewish giant, and the young Brooklyn family with the troubled son.

The exhibition, showcasing her original vision consistently realized, confirms Arbus’s place in the canon of twentieth-century American art. At the risk of sounding retrograde and shamefully pre–post-modern, seeing the exhibition reminded me of T.S. Eliot’s thoughts in “Tradition and the Individual Talent.” Arbus’s work reconfigured the canon when it entered, changing how we look at what came before her (the famous FSA portraits from the Depression era now look stilted) and defining new terrain for those who came after her (think of Nan Goldin, among others).

The presentation of the show, though, leaves much to be desired. As a typical Met installation, this one features dark walls, rooms with little ambient light, and harshly spot lit work. (The show, thankfully, avoids the onerous wall texts regularly seen there.)

Arbus’s photography doesn’t suffer from this presentation as much as work in recent painting shows has, but the collections of her journals and other ephemera are practically unviewable in this environment. Presented in darkened rooms constructed within the large galleries, the items (all lit by overhead spots) fall into a deep shadow when viewers bend over to examine them. I actually yearned for some diffuse florescent lighting in these spaces so that I see the items on display.

Seeing Arbus’s work brought together here gave me a new view of one of her well-known series. In 1969 Arbus began visiting what used to be called “mental hospitals” in New Jersey to photograph the residents. Many of the subjects of these photos have Down Syndrome. Arbus wrote to her daughter about these individuals, “They are the strangest combination of grownup and child I have ever seen.”

Seeing Arbus’s work brought together here gave me a new view of one of her well-known series. In 1969 Arbus began visiting what used to be called “mental hospitals” in New Jersey to photograph the residents. Many of the subjects of these photos have Down Syndrome. Arbus wrote to her daughter about these individuals, “They are the strangest combination of grownup and child I have ever seen.”

These works, installed near the end of the exhibition, provide a jarring moment in the show. They just don’t feel right here. They’re loud. Too loud. Much too loud.

Arbus, prior to this point, had perfected the approach of finding a hint of the grotesque poking through the veneer of normalcy: the young man, looking uncomfortable with himself, wearing a button that says “Bomb Hanoi”; the people next door who happen to spend weekends at a nudist camp; the pursed lip of a heavily made-up Puerto Rican woman hinting at something sinister in her personality.

In the photos of the institutionalized individuals, though, Arbus turns the volume up. With these subjects the difference from society’s norm is abundantly clear, but Arbus chose to square that difference by shooting her subjects in Halloween masks and costumes—adding culture’s most visible manifestation of the grotesque to her strongest flirtation with physical and mental deformity to that point in time. She wrote of these subjects and photos, “It’s the first time I’ve encountered a subject where the multiplicity is the thing.”

In the photos of the institutionalized individuals, though, Arbus turns the volume up. With these subjects the difference from society’s norm is abundantly clear, but Arbus chose to square that difference by shooting her subjects in Halloween masks and costumes—adding culture’s most visible manifestation of the grotesque to her strongest flirtation with physical and mental deformity to that point in time. She wrote of these subjects and photos, “It’s the first time I’ve encountered a subject where the multiplicity is the thing.”

The multiplicity, here, becomes too much. This series is well known. Seen in isolation, the works have a tragic beauty and a power to them. But seen in the context of Arbus’s quieter, more delicate and sensitive work, they screech. They grate like fingers pulled down the chalkboard. They offend.

Arbus mastered the art of looking closely, and sympathetically, at the outsider. That eye is on view throughout the exhibition. In the few rooms that present her portraits of the institutionalized, though, that sensitive eye turns voyeuristic. I had never noticed that change in perspective before. Sometimes it takes seeing a large retrospective for insights like this to arrive.

Diane Arbus Revelations (through May 30, 2005) at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Arbus is best known for her sympathetic photographic portraits of those living on the edges of 1960s American society—from debutante princesses at one end to burlesque performers at the other. Arbus throws in a delightful gaggle of transvestites, ladies who lunch, and nudists for good measure.

The traveling exhibition now at the Met rolls out all of Arbus’s greatest hits: the identical twin girls, the boy with the hand grenade, the Jewish giant, and the young Brooklyn family with the troubled son.

The traveling exhibition now at the Met rolls out all of Arbus’s greatest hits: the identical twin girls, the boy with the hand grenade, the Jewish giant, and the young Brooklyn family with the troubled son.The exhibition, showcasing her original vision consistently realized, confirms Arbus’s place in the canon of twentieth-century American art. At the risk of sounding retrograde and shamefully pre–post-modern, seeing the exhibition reminded me of T.S. Eliot’s thoughts in “Tradition and the Individual Talent.” Arbus’s work reconfigured the canon when it entered, changing how we look at what came before her (the famous FSA portraits from the Depression era now look stilted) and defining new terrain for those who came after her (think of Nan Goldin, among others).

The presentation of the show, though, leaves much to be desired. As a typical Met installation, this one features dark walls, rooms with little ambient light, and harshly spot lit work. (The show, thankfully, avoids the onerous wall texts regularly seen there.)

Arbus’s photography doesn’t suffer from this presentation as much as work in recent painting shows has, but the collections of her journals and other ephemera are practically unviewable in this environment. Presented in darkened rooms constructed within the large galleries, the items (all lit by overhead spots) fall into a deep shadow when viewers bend over to examine them. I actually yearned for some diffuse florescent lighting in these spaces so that I see the items on display.

Seeing Arbus’s work brought together here gave me a new view of one of her well-known series. In 1969 Arbus began visiting what used to be called “mental hospitals” in New Jersey to photograph the residents. Many of the subjects of these photos have Down Syndrome. Arbus wrote to her daughter about these individuals, “They are the strangest combination of grownup and child I have ever seen.”

Seeing Arbus’s work brought together here gave me a new view of one of her well-known series. In 1969 Arbus began visiting what used to be called “mental hospitals” in New Jersey to photograph the residents. Many of the subjects of these photos have Down Syndrome. Arbus wrote to her daughter about these individuals, “They are the strangest combination of grownup and child I have ever seen.”These works, installed near the end of the exhibition, provide a jarring moment in the show. They just don’t feel right here. They’re loud. Too loud. Much too loud.

Arbus, prior to this point, had perfected the approach of finding a hint of the grotesque poking through the veneer of normalcy: the young man, looking uncomfortable with himself, wearing a button that says “Bomb Hanoi”; the people next door who happen to spend weekends at a nudist camp; the pursed lip of a heavily made-up Puerto Rican woman hinting at something sinister in her personality.

In the photos of the institutionalized individuals, though, Arbus turns the volume up. With these subjects the difference from society’s norm is abundantly clear, but Arbus chose to square that difference by shooting her subjects in Halloween masks and costumes—adding culture’s most visible manifestation of the grotesque to her strongest flirtation with physical and mental deformity to that point in time. She wrote of these subjects and photos, “It’s the first time I’ve encountered a subject where the multiplicity is the thing.”

In the photos of the institutionalized individuals, though, Arbus turns the volume up. With these subjects the difference from society’s norm is abundantly clear, but Arbus chose to square that difference by shooting her subjects in Halloween masks and costumes—adding culture’s most visible manifestation of the grotesque to her strongest flirtation with physical and mental deformity to that point in time. She wrote of these subjects and photos, “It’s the first time I’ve encountered a subject where the multiplicity is the thing.”The multiplicity, here, becomes too much. This series is well known. Seen in isolation, the works have a tragic beauty and a power to them. But seen in the context of Arbus’s quieter, more delicate and sensitive work, they screech. They grate like fingers pulled down the chalkboard. They offend.

Arbus mastered the art of looking closely, and sympathetically, at the outsider. That eye is on view throughout the exhibition. In the few rooms that present her portraits of the institutionalized, though, that sensitive eye turns voyeuristic. I had never noticed that change in perspective before. Sometimes it takes seeing a large retrospective for insights like this to arrive.

Diane Arbus Revelations (through May 30, 2005) at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.