Thursday, March 31, 2005

Food for Thought: Half Baked

On the flight home today I worked my way through the March Artforum. The issue contains a couple interesting pieces that piqued and held my interest. I have comments on one tonight, and I’ll follow up with my thoughts on the second tomorrow.

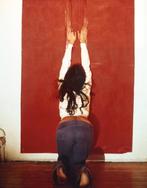

In this issue Kathy O’Dell covers the traveling Ana Mendieta exhibition. In her review of the show, O’Dell comes close to saying in print what many who have seen the show are saying quietly in private—that Mendieta’s work lost its strength and edge after she split with her teacher and lover Hans Breder. O’Dell, though, does not go that far.

In this issue Kathy O’Dell covers the traveling Ana Mendieta exhibition. In her review of the show, O’Dell comes close to saying in print what many who have seen the show are saying quietly in private—that Mendieta’s work lost its strength and edge after she split with her teacher and lover Hans Breder. O’Dell, though, does not go that far.

She raises the issue obliquely, without ever mentioning Mendieta and Breder’s personal relationship. Mendieta’s late work, O’Dell rightly claims, is weak—very weak. Almost half of the period covered by the show she points out (amounting to a third of the work on display) is time that Mendieta spent in Iowa working with Breder. This early student work is actually the best work in her oeuvre. O’Dell leaves it up to her readers to connect the dots.

Since the exhibition first brought together works from across Mendieta’s short life at the Whitney last summer, people have been whispering about the notable fall-off in the quality of her work after she and Breder ended their relationship. No one that I have seen, though, has been willing to open themselves up to the drubbing that will inevitably come from more vocal feminist critics and the goddess crowd if they say this publicly.

It’s a shame that critics and reviewers have felt it necessary to self-censor on this obvious point. All seem to be operating within the confines of the Romantic notion of the artist as a solitary individual creator. If they would be willing to open up their notions of artistic production to explore the nature of collaboration (and to examine how Mendieta fueled Breder’s work as much as he charged hers), Mendieta’s reputation would be enhanced. As the situation stands now, she is being publicly lionized but privately denigrated. That disingenuousness doesn’t serve her reputation, or viewers interested in seeing the show, well.

In this issue Kathy O’Dell covers the traveling Ana Mendieta exhibition. In her review of the show, O’Dell comes close to saying in print what many who have seen the show are saying quietly in private—that Mendieta’s work lost its strength and edge after she split with her teacher and lover Hans Breder. O’Dell, though, does not go that far.

In this issue Kathy O’Dell covers the traveling Ana Mendieta exhibition. In her review of the show, O’Dell comes close to saying in print what many who have seen the show are saying quietly in private—that Mendieta’s work lost its strength and edge after she split with her teacher and lover Hans Breder. O’Dell, though, does not go that far. She raises the issue obliquely, without ever mentioning Mendieta and Breder’s personal relationship. Mendieta’s late work, O’Dell rightly claims, is weak—very weak. Almost half of the period covered by the show she points out (amounting to a third of the work on display) is time that Mendieta spent in Iowa working with Breder. This early student work is actually the best work in her oeuvre. O’Dell leaves it up to her readers to connect the dots.

Since the exhibition first brought together works from across Mendieta’s short life at the Whitney last summer, people have been whispering about the notable fall-off in the quality of her work after she and Breder ended their relationship. No one that I have seen, though, has been willing to open themselves up to the drubbing that will inevitably come from more vocal feminist critics and the goddess crowd if they say this publicly.

It’s a shame that critics and reviewers have felt it necessary to self-censor on this obvious point. All seem to be operating within the confines of the Romantic notion of the artist as a solitary individual creator. If they would be willing to open up their notions of artistic production to explore the nature of collaboration (and to examine how Mendieta fueled Breder’s work as much as he charged hers), Mendieta’s reputation would be enhanced. As the situation stands now, she is being publicly lionized but privately denigrated. That disingenuousness doesn’t serve her reputation, or viewers interested in seeing the show, well.