Saturday, October 29, 2005

Cautionary Tales

The Internets are good for more than just spreading rumors. They're also good for spreading advice. So take some:

- If an artist offers to swap you new work for old, do it.

- If the Guggenheim asks you to lend it work, don't do it (via).

- If you're thinking about inviting that OC Art Blog guy to your Halloween party, think again. Ewww.

Tuesday, October 25, 2005

Those Weak, Weepy Bloggers

What's going on here? Is it something in the rarefied air of the blogosphere?

First, I admit to getting all teared up by Janet Cardiff's Forty-Part Motet, and then Edward admits to the same while watching the new Shirin Neshat video.

Start by reading his excellent piece. Then select one or more options from the following list.

I think that all these sissy-boy art bloggers ought to toughen up and:

First, I admit to getting all teared up by Janet Cardiff's Forty-Part Motet, and then Edward admits to the same while watching the new Shirin Neshat video.

Start by reading his excellent piece. Then select one or more options from the following list.

I think that all these sissy-boy art bloggers ought to toughen up and:

- Spend their free time watching football instead of hanging out in museums and galleries

- Quit ordering cosmos and start drinking Bud

- Realize that everyone belches; go ahead and do it with gusto when the need arises

- Accept the fact that NASCAR isn't just for Southerners anymore

- Give up that subscription to Artforum and start reading Maxim instead

Sunday, October 23, 2005

Editing the Subtitles

Museum exhibitions often get their subtitles when someone in the marketing department realizes she has to sell the show. Don't you think critics ought to give the subtitles instead? That way the public would have a better idea of what they'll really get for a $20 admission.

In that spirit, here are more appropriate subtitles for two stinkers that I saw today.

In that spirit, here are more appropriate subtitles for two stinkers that I saw today.

- At the Whitney, "Oscar Bluemner: A Passion for Red Buildings"

- At MoMA, "Elizabeth Murray: Prelude to Pixar"

Thursday, October 20, 2005

The Church and Contemporary Art

Last weekend’s Financial Times Magazine ran quite an interesting piece (not available on-line) by Rachel Spence on how Italy’s Roman Catholic Church is positioning itself in relation to contemporary art.

The church, of course, was the greatest of arts patrons for much of the second millennium. That changed, though, during the nineteenth century. Spence quotes Monsignor Timothy Verdon, director of the Office for Evangelization Through Art in the Florence Archdiocese, on why this is. “The Church found itself patronizing artists who were opposed to the avant-garde,” Verdon says. “The image it projected between the 1830s and 1940s was backward-looking in an age that increasingly felt the past was irrelevant.”

As part of Vatican II, Pope Paul VI attempted to change this situation with an affirmation of contemporary art’s place in the liturgy, but local clergy did not embrace the new. What emerged, according to Verdon, was “a sad parody of contemporaneity in the vestigial echoes of Fra Agelico style.”

The most interesting part of Spence’s piece, though is the discussion of the church’s strong preference for figuration over abstraction. The church’s official position is that artwork must “express the liturgy,” and as a result those charged with commissioning art for church spaces tend to default to figurative work.

Spence quotes a priest from an Italian parish explaining why liturgical art should be figurative. “The Church, in general,” he says, “is for simple people and they must be able to understand.” (This patronizing of parishioners might help explain why regular church attendance across Italy declined from 70% of the population to 40% over the second half of the last century.)

But it’s not only the Italian church that struggles with how to integrate art into the liturgy to create a suitable worship experience. Closer to home, New York artist Gwyneth Leech has received criticism recently over a cycle of figurative paintings representing the stations of the cross. Commissioned by an Episcopal church, Saint Paul’s on the Green, in Norwalk, CT, Leech chose not only to set the paintings in the present day (a tradition that goes back to the middle ages), but also to situate the narrative in the context of war. (Station 1: Jesus is Condemned to Death is at right.)

But it’s not only the Italian church that struggles with how to integrate art into the liturgy to create a suitable worship experience. Closer to home, New York artist Gwyneth Leech has received criticism recently over a cycle of figurative paintings representing the stations of the cross. Commissioned by an Episcopal church, Saint Paul’s on the Green, in Norwalk, CT, Leech chose not only to set the paintings in the present day (a tradition that goes back to the middle ages), but also to situate the narrative in the context of war. (Station 1: Jesus is Condemned to Death is at right.)

Of her choices, Leech says, “I was asked to combine the traditional stations iconography with elements of the world we live in. This brief eventually led to my vision of Christ as a prisoner of war, and as a hostage tortured by insurgents. The crowds are refugees. The people weeping at the foot of the cross are grieving Iraqis and Americans who have lost family members to bombs and to violence.”

The question of how well Leech’s contemporary iconography integrates with the historical narrative remains open. There is no question, though, that Leech’s paintings have caused controversy in Norwalk. The reason for this, I believe, is similar to the reason that the Italian priest gave for restricting liturgical art to figuration: certain people are not able to see an object, understand metaphor, and make the leap to the concept that stands behind the object at hand.

Corporate curators made a realization half a century ago. By replacing figuration with abstraction in the art they commissioned for public buildings, they were able to remove the possibility that conflict would arise about the art’s subject matter. It might be time for the church to examine that strategy now—and to rethink whether the liturgy must be supported with representational art.

But there would be a secondary benefit as well. In her FT piece Spence quotes Danilo Eccher, director of Rome’s Museum of Contemporary Art on the applicability of figuration for today’s religious art. “Medieval man needed frescoed churches because at home he had nothing, but we are bombarded daily by images. Contemporary man therefore has need of a space for secret emotion, in silence more than in image.” What better way to create a meditative space suitable for worship than to remove all reference to the stresses of the everyday world?

The church, of course, was the greatest of arts patrons for much of the second millennium. That changed, though, during the nineteenth century. Spence quotes Monsignor Timothy Verdon, director of the Office for Evangelization Through Art in the Florence Archdiocese, on why this is. “The Church found itself patronizing artists who were opposed to the avant-garde,” Verdon says. “The image it projected between the 1830s and 1940s was backward-looking in an age that increasingly felt the past was irrelevant.”

As part of Vatican II, Pope Paul VI attempted to change this situation with an affirmation of contemporary art’s place in the liturgy, but local clergy did not embrace the new. What emerged, according to Verdon, was “a sad parody of contemporaneity in the vestigial echoes of Fra Agelico style.”

The most interesting part of Spence’s piece, though is the discussion of the church’s strong preference for figuration over abstraction. The church’s official position is that artwork must “express the liturgy,” and as a result those charged with commissioning art for church spaces tend to default to figurative work.

Spence quotes a priest from an Italian parish explaining why liturgical art should be figurative. “The Church, in general,” he says, “is for simple people and they must be able to understand.” (This patronizing of parishioners might help explain why regular church attendance across Italy declined from 70% of the population to 40% over the second half of the last century.)

But it’s not only the Italian church that struggles with how to integrate art into the liturgy to create a suitable worship experience. Closer to home, New York artist Gwyneth Leech has received criticism recently over a cycle of figurative paintings representing the stations of the cross. Commissioned by an Episcopal church, Saint Paul’s on the Green, in Norwalk, CT, Leech chose not only to set the paintings in the present day (a tradition that goes back to the middle ages), but also to situate the narrative in the context of war. (Station 1: Jesus is Condemned to Death is at right.)

But it’s not only the Italian church that struggles with how to integrate art into the liturgy to create a suitable worship experience. Closer to home, New York artist Gwyneth Leech has received criticism recently over a cycle of figurative paintings representing the stations of the cross. Commissioned by an Episcopal church, Saint Paul’s on the Green, in Norwalk, CT, Leech chose not only to set the paintings in the present day (a tradition that goes back to the middle ages), but also to situate the narrative in the context of war. (Station 1: Jesus is Condemned to Death is at right.)Of her choices, Leech says, “I was asked to combine the traditional stations iconography with elements of the world we live in. This brief eventually led to my vision of Christ as a prisoner of war, and as a hostage tortured by insurgents. The crowds are refugees. The people weeping at the foot of the cross are grieving Iraqis and Americans who have lost family members to bombs and to violence.”

The question of how well Leech’s contemporary iconography integrates with the historical narrative remains open. There is no question, though, that Leech’s paintings have caused controversy in Norwalk. The reason for this, I believe, is similar to the reason that the Italian priest gave for restricting liturgical art to figuration: certain people are not able to see an object, understand metaphor, and make the leap to the concept that stands behind the object at hand.

Corporate curators made a realization half a century ago. By replacing figuration with abstraction in the art they commissioned for public buildings, they were able to remove the possibility that conflict would arise about the art’s subject matter. It might be time for the church to examine that strategy now—and to rethink whether the liturgy must be supported with representational art.

But there would be a secondary benefit as well. In her FT piece Spence quotes Danilo Eccher, director of Rome’s Museum of Contemporary Art on the applicability of figuration for today’s religious art. “Medieval man needed frescoed churches because at home he had nothing, but we are bombarded daily by images. Contemporary man therefore has need of a space for secret emotion, in silence more than in image.” What better way to create a meditative space suitable for worship than to remove all reference to the stresses of the everyday world?

Tuesday, October 18, 2005

The Forty-Part Motet

With its recent installation of Janet Cardiff's The Forty-Part Motet MoMA has created what has to be one of the most sublimely beautiful spaces in Midtown Manhattan. (An installation view is at right.) It's not fashionable these days to use words like "sublime" and "beautiful" without scare quotes, but I'm simply at a loss for how to describe the work without them.

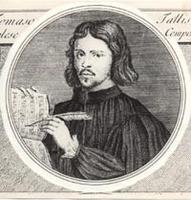

With its recent installation of Janet Cardiff's The Forty-Part Motet MoMA has created what has to be one of the most sublimely beautiful spaces in Midtown Manhattan. (An installation view is at right.) It's not fashionable these days to use words like "sublime" and "beautiful" without scare quotes, but I'm simply at a loss for how to describe the work without them.Cardiff's piece, for those not familiar with this well-traveled sound installation, is a recording of Thomas Tallis's polyphonic choral work from 1575, Spem in alium. Tallis's Latin text translates this way:

I have never put my hope in any other but in you God of Israel who will be angry and yet become again gracious and who forgives all the sins of suffering man. Lord God Creator of Heaven and Earth look upon our lowliness.For this piece, Cardiff recorded each of the forty unique vocal parts individually. The installation consists of forty speakers arranged in an oval, each speaker playing back a voice of one member of the Salisbury Cathedral Choir. Cardiff's advanced recording and playback technology creates the experience of a live performance that typical two-channel playback cannot. The elliptical installation gives visitors the ability to move around and through the sound in a way that is not possible when the piece is performed by a live choir.

Simply put, the recording stuns. If, as the choir crescendos, you don't feel a shiver rise somewhere inside you, you have to be emotionally tone deaf. Both times I've visited the piece in the last few weeks, I've fought to hold back an involuntary display of emotion. As I struggled to keep my eyes dry, I looked around the gallery space and saw others furtively wiping their eyes, hoping that no one else was noticing.

I've already decided that while this piece is installed over the next year it will become a regular lunch hour stop when I am working in New York. I'll be curious to see, though, just how my reaction to the piece will change the more that I experience it because in trying to determine what about the piece gives it such emotional power, I've realized that it's not anything in Cardiff's work.

The Forty-Part Motet takes all of its emotional punch from the choir's performance of Tallis's piece. Most serious singers include Spem in alium on the short list of works they want to perform some day because the piece creates a sound environment that is unique and that (prior to Cardiff's work) could not be adequately reproduced using recording technology.

The Forty-Part Motet takes all of its emotional punch from the choir's performance of Tallis's piece. Most serious singers include Spem in alium on the short list of works they want to perform some day because the piece creates a sound environment that is unique and that (prior to Cardiff's work) could not be adequately reproduced using recording technology.In her piece Cardiff has harnessed the power of a live performance by using the skills of a master recording technician. She does not add to the effect of a live performance of Spem in alium; rather, she optimizes the recording of the performance to recreate the effect of a live event better than any recording engineer has been able to do to date. Unlike her other work where she creates original sound environments, here Cardiff has recreated a sound environment originally developed over 400 years ago.

Filtered through Cardiff's technology, the music sounds good enough to make listeners choke up. I can't help but wonder, though, if I will continue to have that experience over repeated visits. I still become emotional every time I hear the final movement of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony performed live. But that only happens for me a couple times a decade. I wonder if listening to Cardiff's recording of Spem in alium once a week over the next year in this walk-in sound chamber will dull my sensibilities to the work. I question whether the technological mediation of my experience of the piece of music will get in the way of my continued appreciation for the performance that has been recorded.

The magic of a live performance (recreated so well here) may be just that--magic created by real people in a passing moment in time. When that performance repeats exactly every fourteen minutes all day every day, the magic may dissipate. Only time will tell if Cardiff's piece has the staying power of the original, unmediated Spem in alium. I hope that it does, but I'm not sure that it will.

Monday, October 17, 2005

Current Chelsea Picks

A few hours wandering around Chelsea Saturday afternoon, and I was only able to come up with two and a half exhibitions worth recommending.

Adam Cvijanovic’s latest show at Bellwether, Love Poem (10 Minutes After the End of Gravity), has received ample coverage since it opened. There’s good reason for that. His 14 x 75 foot painting on Tyvek (at right) feels like a reimagined, apocalyptic version of an early-1970s realist piece. The staples of suburban America (tract homes, cars, and consumer products ranging from bottles of Diet Coke to Pop Tart boxes to Glad trash bags) become weightless detritus as they float off into space, unmoored after the suspension of the law of gravity. This feels like a painting that would never have been done if it weren’t for the events of September 2001 when we realized that disasters did not have to be solely of the predictable, natural type.

Adam Cvijanovic’s latest show at Bellwether, Love Poem (10 Minutes After the End of Gravity), has received ample coverage since it opened. There’s good reason for that. His 14 x 75 foot painting on Tyvek (at right) feels like a reimagined, apocalyptic version of an early-1970s realist piece. The staples of suburban America (tract homes, cars, and consumer products ranging from bottles of Diet Coke to Pop Tart boxes to Glad trash bags) become weightless detritus as they float off into space, unmoored after the suspension of the law of gravity. This feels like a painting that would never have been done if it weren’t for the events of September 2001 when we realized that disasters did not have to be solely of the predictable, natural type.

Jeremy Blake’s newest film, Sodium Fox, is showing at Feigen Contemporary, and it shouldn’t be missed. Don’t bother with the static works in the front gallery, though. Head straight to the rear room where the film is being screened. Blake’s video work is all about mood, atmosphere, and the movement of color over time. The stills for sale out front do not, and cannot, do justice to the mesmerizing experience of watching his contemporary consumeristic landscape emerge and morph.

I also liked several things in the inaugural group exhibition, Set It Off, at the new James Nicholson Gallery. But since I already wrote about half the pieces in the show, I’m not going to plug them again. I’ll just say that it looks like someone took the advice in my final paragraph, cherry-picked the best work from last summer’s Artists In the Marketplace (AIM 25) exhibition, and stuck price tags on the pieces. That’s proof, I guess, that the Bronx Museum program works.

Adam Cvijanovic’s latest show at Bellwether, Love Poem (10 Minutes After the End of Gravity), has received ample coverage since it opened. There’s good reason for that. His 14 x 75 foot painting on Tyvek (at right) feels like a reimagined, apocalyptic version of an early-1970s realist piece. The staples of suburban America (tract homes, cars, and consumer products ranging from bottles of Diet Coke to Pop Tart boxes to Glad trash bags) become weightless detritus as they float off into space, unmoored after the suspension of the law of gravity. This feels like a painting that would never have been done if it weren’t for the events of September 2001 when we realized that disasters did not have to be solely of the predictable, natural type.

Adam Cvijanovic’s latest show at Bellwether, Love Poem (10 Minutes After the End of Gravity), has received ample coverage since it opened. There’s good reason for that. His 14 x 75 foot painting on Tyvek (at right) feels like a reimagined, apocalyptic version of an early-1970s realist piece. The staples of suburban America (tract homes, cars, and consumer products ranging from bottles of Diet Coke to Pop Tart boxes to Glad trash bags) become weightless detritus as they float off into space, unmoored after the suspension of the law of gravity. This feels like a painting that would never have been done if it weren’t for the events of September 2001 when we realized that disasters did not have to be solely of the predictable, natural type.Jeremy Blake’s newest film, Sodium Fox, is showing at Feigen Contemporary, and it shouldn’t be missed. Don’t bother with the static works in the front gallery, though. Head straight to the rear room where the film is being screened. Blake’s video work is all about mood, atmosphere, and the movement of color over time. The stills for sale out front do not, and cannot, do justice to the mesmerizing experience of watching his contemporary consumeristic landscape emerge and morph.

I also liked several things in the inaugural group exhibition, Set It Off, at the new James Nicholson Gallery. But since I already wrote about half the pieces in the show, I’m not going to plug them again. I’ll just say that it looks like someone took the advice in my final paragraph, cherry-picked the best work from last summer’s Artists In the Marketplace (AIM 25) exhibition, and stuck price tags on the pieces. That’s proof, I guess, that the Bronx Museum program works.

Monday, October 10, 2005

Slow Week

I've drawn the travel straw again this week which means that posting will be light. I do, though, have something in the works on MoMA's new installation of the contemporary galleries that I will finish off as time (and jet lag) allows.

Update: No sooner do I post the above than MAN goes ahead and runs my piece. Well, it's not exactly my piece because I hadn't actually written it yet. But Tyler says almost exactly what I had intended to say about MoMA's new installation in this post from this morning. So follow the link and read him. I do, though, have more in-depth thoughts on Janet Cardiff's The Forty-Part Motet that I will run later this week.

Update: No sooner do I post the above than MAN goes ahead and runs my piece. Well, it's not exactly my piece because I hadn't actually written it yet. But Tyler says almost exactly what I had intended to say about MoMA's new installation in this post from this morning. So follow the link and read him. I do, though, have more in-depth thoughts on Janet Cardiff's The Forty-Part Motet that I will run later this week.

Friday, October 07, 2005

Two Worth Reading

NYFA Current is out with a special issue this week that contains an interview with gallerists Don Carroll of Jack the Pelican Presents and Christian Haye of Projectile. The piece offers excellent advice for artists looking to establish gallery representation.

Greg gets all righteously indignant (and justifiably so) over the destruction of a landmark piece of modernist residential architecture--Gordon Bunshaft's Travertine House. Martha deserves another trip to the pokey for her role in this one.

Greg gets all righteously indignant (and justifiably so) over the destruction of a landmark piece of modernist residential architecture--Gordon Bunshaft's Travertine House. Martha deserves another trip to the pokey for her role in this one.

Thursday, October 06, 2005

BCN Notes

Last week I promised notes on a few Barcelona art spots. Here are sound bites on three.

Parc Güell: Antonio Gaudí's work fascinates me because of its utter originality. His slightly warped melding of natural and man-made forms into built spaces (the park's gatehouse is at right) is unlike anything anyone had done before or since. His work on this park opens a dialogue between landscape and structural architecture that is conducted in Gaudí's own private language. I'm not sure I understand everything he says, but it sure is fun to listen.

Parc Güell: Antonio Gaudí's work fascinates me because of its utter originality. His slightly warped melding of natural and man-made forms into built spaces (the park's gatehouse is at right) is unlike anything anyone had done before or since. His work on this park opens a dialogue between landscape and structural architecture that is conducted in Gaudí's own private language. I'm not sure I understand everything he says, but it sure is fun to listen.

The Picasso Museum: If you want to see Picasso qua Picasso, you're better off going to MoMA. But walking through the extensive collection of pre-Blue Period work here (donated by Picasso himself in 1970) allows you to see Picasso becoming Picasso in a way that you can't anywhere else.

National Museum of Catalunian Art: I'm prone to be suspect of collections that are assembled and curated for nationalistic purposes. So I was pleasantly surprised by the incredible quality, richness, and depth of work at MNAC. With pieces spanning the 12th to the mid-20th century, the museum's collection can really stand on its own against any historical collection worldwide--which is probably just what the Catalunian government wants me to say about it.

Parc Güell: Antonio Gaudí's work fascinates me because of its utter originality. His slightly warped melding of natural and man-made forms into built spaces (the park's gatehouse is at right) is unlike anything anyone had done before or since. His work on this park opens a dialogue between landscape and structural architecture that is conducted in Gaudí's own private language. I'm not sure I understand everything he says, but it sure is fun to listen.

Parc Güell: Antonio Gaudí's work fascinates me because of its utter originality. His slightly warped melding of natural and man-made forms into built spaces (the park's gatehouse is at right) is unlike anything anyone had done before or since. His work on this park opens a dialogue between landscape and structural architecture that is conducted in Gaudí's own private language. I'm not sure I understand everything he says, but it sure is fun to listen.The Picasso Museum: If you want to see Picasso qua Picasso, you're better off going to MoMA. But walking through the extensive collection of pre-Blue Period work here (donated by Picasso himself in 1970) allows you to see Picasso becoming Picasso in a way that you can't anywhere else.

National Museum of Catalunian Art: I'm prone to be suspect of collections that are assembled and curated for nationalistic purposes. So I was pleasantly surprised by the incredible quality, richness, and depth of work at MNAC. With pieces spanning the 12th to the mid-20th century, the museum's collection can really stand on its own against any historical collection worldwide--which is probably just what the Catalunian government wants me to say about it.

Wednesday, October 05, 2005

Gettygate

I've been staying away from posting about current events at the Getty because the situation is being covered so exhaustively by the LA Times and on Modern Art Notes (see here, for example, for yesterday's brief). But there's one more reason I haven't touched the topic: it pains me to think about just what a f--ed up mess Barry Munitz has created of that venerable institution.

As the revelations keep coming, though, I can't help but think that we've heard this whole story before. A low-level operative gets busted for committing a crime. Some diligent, sleuthing local reporters continue to chase the story, following it all the way to the top. Eventually the leader steps aside as criminal prosecution appears imminent.

As the revelations keep coming, though, I can't help but think that we've heard this whole story before. A low-level operative gets busted for committing a crime. Some diligent, sleuthing local reporters continue to chase the story, following it all the way to the top. Eventually the leader steps aside as criminal prosecution appears imminent.

If you're interested in drama and suspense here, you might as well change the channel. We all know how this one is going to end, thanks to Woodward and Bernstein's playbook. Let's just hope the journalists at the LA Times stick to the game plan: 1) follow the money and 2) keep asking, "What did the president know and when did he know it?" The sooner they can press Nixon to step onto Marine One to fly off into the sunset, the better. And this time there's not going to be a crony waiting at the ready with a Get out of Jail Free card.

As the revelations keep coming, though, I can't help but think that we've heard this whole story before. A low-level operative gets busted for committing a crime. Some diligent, sleuthing local reporters continue to chase the story, following it all the way to the top. Eventually the leader steps aside as criminal prosecution appears imminent.

As the revelations keep coming, though, I can't help but think that we've heard this whole story before. A low-level operative gets busted for committing a crime. Some diligent, sleuthing local reporters continue to chase the story, following it all the way to the top. Eventually the leader steps aside as criminal prosecution appears imminent.If you're interested in drama and suspense here, you might as well change the channel. We all know how this one is going to end, thanks to Woodward and Bernstein's playbook. Let's just hope the journalists at the LA Times stick to the game plan: 1) follow the money and 2) keep asking, "What did the president know and when did he know it?" The sooner they can press Nixon to step onto Marine One to fly off into the sunset, the better. And this time there's not going to be a crony waiting at the ready with a Get out of Jail Free card.

Tuesday, October 04, 2005

A Lesson to Learn from Boston's Mistake

Unlike a few of us around the blogosphere who had an immediate, reactionary response to the MFA Boston's new show "Things I Love," Modern Kicks decided to give the show a chance and actually see it before weighing in with commentary.

Don't miss the review that has been posted there. The author raises several interesting and valid points that those of us who haven't seen the show wouldn't have been able to make. He weighs in with this final comment, "But the problem isn't one of ethics, as it sometimes is portrayed, at least not at the root: rather, it's a one of judgment and taste."

Museums can take away an important lesson from JL's commentary: pick your potential donors carefully. It sounds like the MFA hasn't done an especially good job of that in this case.

Don't miss the review that has been posted there. The author raises several interesting and valid points that those of us who haven't seen the show wouldn't have been able to make. He weighs in with this final comment, "But the problem isn't one of ethics, as it sometimes is portrayed, at least not at the root: rather, it's a one of judgment and taste."

Museums can take away an important lesson from JL's commentary: pick your potential donors carefully. It sounds like the MFA hasn't done an especially good job of that in this case.

Monday, October 03, 2005

World Weary and Wondering

I'm back home in New York this week after three weeks away. During that time I had very limited access to the Internet and no access to English-language broadcast journalism. Apart from a couple issues of The International Herald Tribune, I didn't have access to English-language daily print media either.

Three weeks isn't really a long time, but during that period I came to feel horribly out of the art world loop: no Artnet or ArtInfo, only the briefest of moments to skim the Arts section of The New York Times on-line, and (aside from one or two of my favorites) no blogs. I missed the whole fall opening season in Chelsea, and I'm still grumbling about not being able to see Floating Island.

I had wanted to get out to see a few shows last Saturday in Williamsburg and Chelsea, but I wasn't able to make that happen. I did, though, have a chance to open my blog aggregator for the first time in weeks and spent some time trolling through the hundreds of posts I didn't see as they were published last month. I don't yet feel caught up with all that I missed last month, and I don't quite feel like I will be able to catch up fully.

It didn't used to be that way. I'm not thinking about the situation at some point in the distant past here. I'm remembering only as far back as the spring and summer of 2004.

Just a little more than a year ago, when I started this blog, there were probably less than 20 art blogs being published. Using an aggregator it was possible to read through the universe of art blogs once a week in a 30 minute sitting. Now, I hear, there are over 400 art-related blogs being published. I have a hard time keeping up with the good ones every week--let alone with the other 380 out there. Artnet is publishing must-read content just as frequently as ever--if not more so. ArtInfo now provides pointers to many additional items every day, doubling or tripling the number that ArtsJournal already highlights. And then there are the monthly glossies to skim through. It feels like there is an order of magnitude more information that needs to be managed on a daily basis today to remain an insider than there was only a year ago.

A similar explosion has happened on the gallery scene in Chelsea. Before I started the blog, I could pretty much cover Chelsea in a part of a day. (Granted, when I do a comprehensive gallery run through it really is that. I'm in and out of a gallery in less than a minute if I don't see something that interests me.) I can't do that any more. With new spaces and new buildings on whole new streets, I can't cover the neighborhood thoroughly in a day anymore.

All this makes me wonder two things. First, if I will ever get back ahead of the curve--especially with more overseas travel on the calendar. And, second, if there is really enough interest in contemporary art today to support all the galleries and sources of commentary that have emerged in just the last year.

I think the answer to the first is "yes," with time. I'm not so sure that the answer to the second is the same.

Three weeks isn't really a long time, but during that period I came to feel horribly out of the art world loop: no Artnet or ArtInfo, only the briefest of moments to skim the Arts section of The New York Times on-line, and (aside from one or two of my favorites) no blogs. I missed the whole fall opening season in Chelsea, and I'm still grumbling about not being able to see Floating Island.

I had wanted to get out to see a few shows last Saturday in Williamsburg and Chelsea, but I wasn't able to make that happen. I did, though, have a chance to open my blog aggregator for the first time in weeks and spent some time trolling through the hundreds of posts I didn't see as they were published last month. I don't yet feel caught up with all that I missed last month, and I don't quite feel like I will be able to catch up fully.

It didn't used to be that way. I'm not thinking about the situation at some point in the distant past here. I'm remembering only as far back as the spring and summer of 2004.

Just a little more than a year ago, when I started this blog, there were probably less than 20 art blogs being published. Using an aggregator it was possible to read through the universe of art blogs once a week in a 30 minute sitting. Now, I hear, there are over 400 art-related blogs being published. I have a hard time keeping up with the good ones every week--let alone with the other 380 out there. Artnet is publishing must-read content just as frequently as ever--if not more so. ArtInfo now provides pointers to many additional items every day, doubling or tripling the number that ArtsJournal already highlights. And then there are the monthly glossies to skim through. It feels like there is an order of magnitude more information that needs to be managed on a daily basis today to remain an insider than there was only a year ago.

A similar explosion has happened on the gallery scene in Chelsea. Before I started the blog, I could pretty much cover Chelsea in a part of a day. (Granted, when I do a comprehensive gallery run through it really is that. I'm in and out of a gallery in less than a minute if I don't see something that interests me.) I can't do that any more. With new spaces and new buildings on whole new streets, I can't cover the neighborhood thoroughly in a day anymore.

All this makes me wonder two things. First, if I will ever get back ahead of the curve--especially with more overseas travel on the calendar. And, second, if there is really enough interest in contemporary art today to support all the galleries and sources of commentary that have emerged in just the last year.

I think the answer to the first is "yes," with time. I'm not so sure that the answer to the second is the same.